Every year the headlines get louder: severe heat waves, shrinking ice sheets, and governments making promises that feel too slow. But right now, the truth is clearer than ever—we don’t have to wait for politicians or corporations to save us. The choices we make every day, from what we eat to how we move around, are powerful tools for shaping a healthier planet and a healthier life.

The good news? Many of the actions that cut emissions also save money, improve our wellbeing, and make our communities better places to live. This isn’t about sacrifice—it’s about smarter, more sustainable living that benefits us all right now. As author Steven Earle points out in this excerpt from Runaway Climate, there are many ways we can take personal action—practical, everyday steps that put climate solutions directly into our own hands. Let’s explore the simple, meaningful changes that can help us tackle climate change while making life more vibrant and rewarding.

What Do We Need To Do?

If we gave up eating beef we would have roughly 20 to 30 times more land for food than we have now.

—James Lovelock

The clear message from the preceding chapters is that if we hope to avoid the dangerous climate change that is predicted by climate scientists, or the much more devastating scenario that would come crashing down on us during a PETM-like runaway climate catastrophe, we need to do something, and we need to do it now. Not soon. Now! But what can we do? Is it more important for us all to make individual changes, or for governments to tighten the rules on emissions, or for industry to make big changes? The answer, of course, is all three.

Governments control the levers that will bring about major changes, but they are excruciatingly slow to pull them, and the results take a long time to come into effect. Industry, which, with a few exceptions, is motivated almost entirely by profit, will not change until forced to, either by rules or by the market. On the other hand, we control the levers for smaller-scale personal changes, and we can make quick decisions to modify our lives in ways that will have an immediate effect. What’s more, we are the market, and we elect the government (in some places at least).

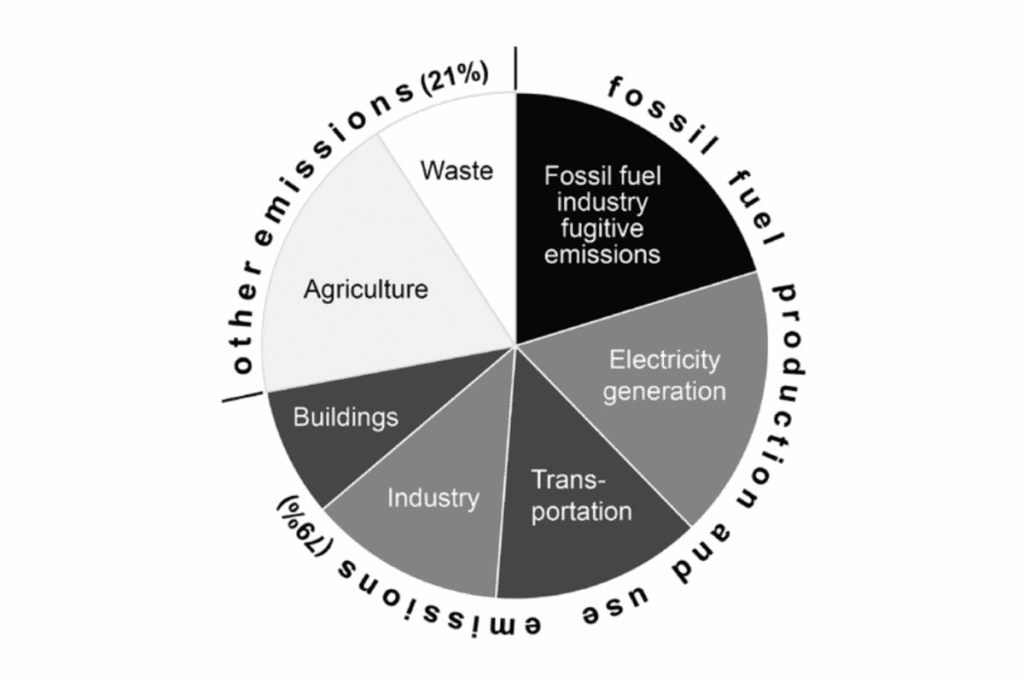

The main sources of our GHG emissions are summarized on figure 11.1. Fossil fuel production and use accounts for 79% of anthropogenic GHG warming on Earth. Obviously, we need to quickly end our use of fossil fuels. Doing that has may co-benefits, as summarized below, and it will take a bonus bite out of our climate impact because it will also curtail most of the fugitive emissions from fossil fuel production.

Of course, we can’t forget emissions from agriculture and waste, but those too are possible to reduce, and the required changes are largely in our hands. For more about our GHG emissions please refer to section 4 of the appendix.

Personal Actions

There are some aspects of our personal emissions that we cannot change easily or quickly, such as energy use in our homes, and especially where that energy comes from, but many others are under our control, and can be changed very quickly, at least by individuals, if not by entire communities.

But before we go there, here’s something to think about. What if it turns out that climate scientists have got it all wrong, and that people who write books like this one, and speak to community organizations, and organize marches are full of bunk? What if you actually listen to us and make significant changes to your life, like driving way less and walking or biking more, or eating less meat and more vegetables, or renovating your house to make it more energy efficient, and then it turns out you didn’t need to do any of those stupid things, and that the so-called climate problem will fix itself? What a bummer! You would end up being fitter and healthier, the air you breathe and the water you drink would be cleaner, some farmland now used to feed or raise beef cows might get returned to forests or even parks, and your home would be more comfortable and cheaper to live in—all for no damn good reason! The message, of course, is that many of the personal changes that we must make to reduce our climate impacts can be win-win-win changes that will also benefit us and our immediate environment. In other words, they are changes that we should embrace regardless of our concern for the climate. We’ll focus on some of those.

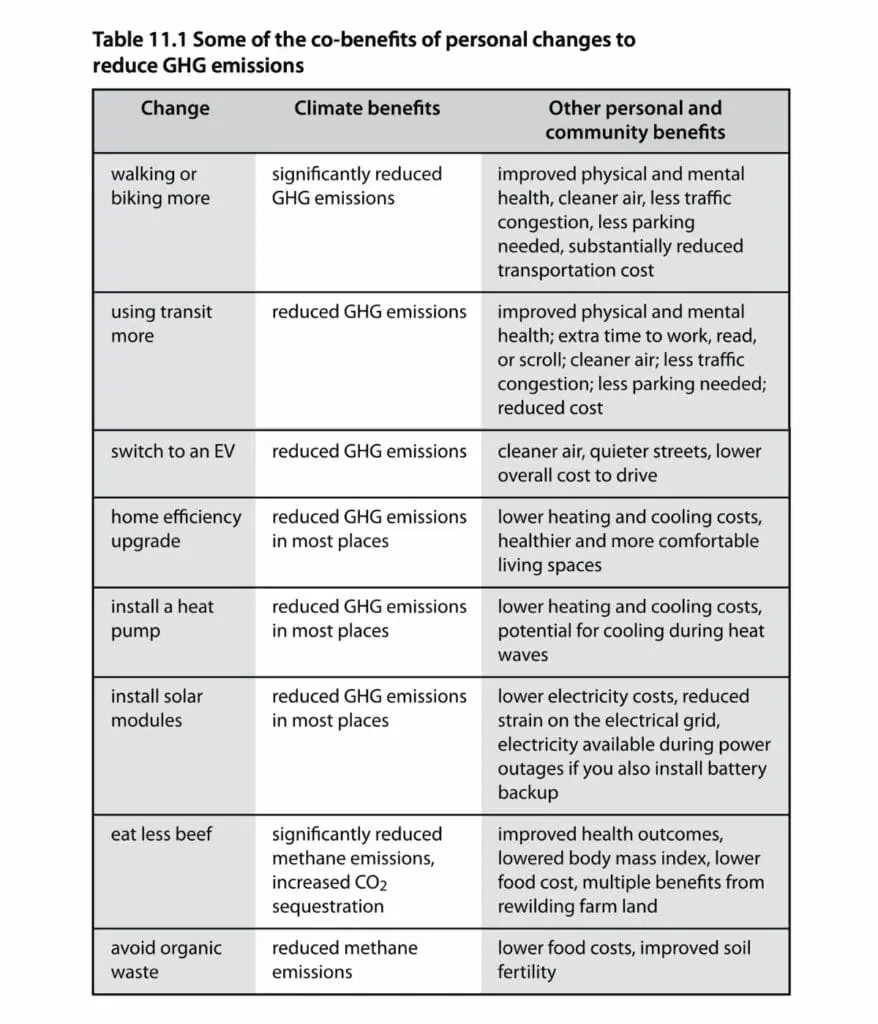

How about walking or biking to work, or to shop, or to college? That’s so much better for your physical and mental health than sitting in a car and swearing at the traffic! If you’re not ready to pedal up those hills, an electric bike can help. You’ll save a lot of money on fuel and vehicle maintenance. You might qualify for a reduced insurance rate if you’re not driving your car to work every day, or you might even be able to divorce your car. You’ll get to feel the seasons go by (the good and the bad!) and experience how your community changes from month to month. Some of the benefits of switching modes of transportation (and other solutions) are summarized in table 11.1.

OK, not ready to walk or bike. How about catching the bus? First, you’ll have to walk a distance to the bus stop, and maybe at the other end as well. That little bit of walking, in fact, is one of the greatest health benefits of using transit. The whole trip might take a little longer, but you’ll get most of that time back because you can do things on the bus that you can’t do while driving. It will almost certainly cost you less per trip. Yes, transit schedules and routes are not what they could be— especially in North America—but if more people started using buses and trains, transit would get better.

Transit doesn’t work for you? How about an electric car? Yes, they are expensive, but that cost will be repaid in reduced fuel and maintenance costs. EV costs are coming down, and within a decade or so, you won’t be able to buy a new fossil-fueled car anyway. In addition to reducing GHGs, faster adoption of EVs will also make our streets quieter and the air easier to breathe. An illustration of the dramatic public health benefits of reducing local pollution that we could gain by curtailing our use of fossil fuel powered vehicles—through more cycling and walking, greater use of public transit, and the switch to electric vehicles—is provided in box 11.1.

What about where you live? Is your home energy efficient? Is it bigger than what you really need? Could you benefit from moving closer to work or school or shopping? Does your roof have solar potential?

Surely, we don’t need a pandemic to force us into changing our transportation modes so that we can all benefit from positive health outcomes! We just need to reach the inevitable conclusion that driving fossil-fueled vehicles is very bad for our collective health and for the planet’s health. And that’s not just because of the pollution they cause.

How does taking on climate change impact our health overall? The authors of a recent study published in The Lancet added up the expected health impacts of the UK’s plan to be carbon neutral by 2050.7 They point out that carbon-reduction measures benefit the health of a population because the air will be cleaner, people will be more physically active, homes will be better insulated and so more comfortable, and people will eat less meat and dairy and more fruit and vegetables. They estimate that the most aggressive planned pathway to net-zero by 2050 will result in over 13 million life-years gained by the population of England and Wales by 2100.]

If your home is older, you could save a lot of energy by upgrading with better windows, reducing leakage with weatherstripping and caulking, or by adding insulation to the walls and attic. You could install a more efficient heating and/or cooling system, such as a heat pump. Many jurisdictions already have incentives to make such changes. If much of your electricity comes from fossil-fuel sources (which still applies in most states, some provinces, and many countries), then putting solar modules on your roof can make a big GHG difference and save you money. Solar electricity is cost-effective in most parts of North America and Europe, even in places where it seems to be raining much of the time.8 The benefits and co -benefits of some of these options are summarized in table 11.1.

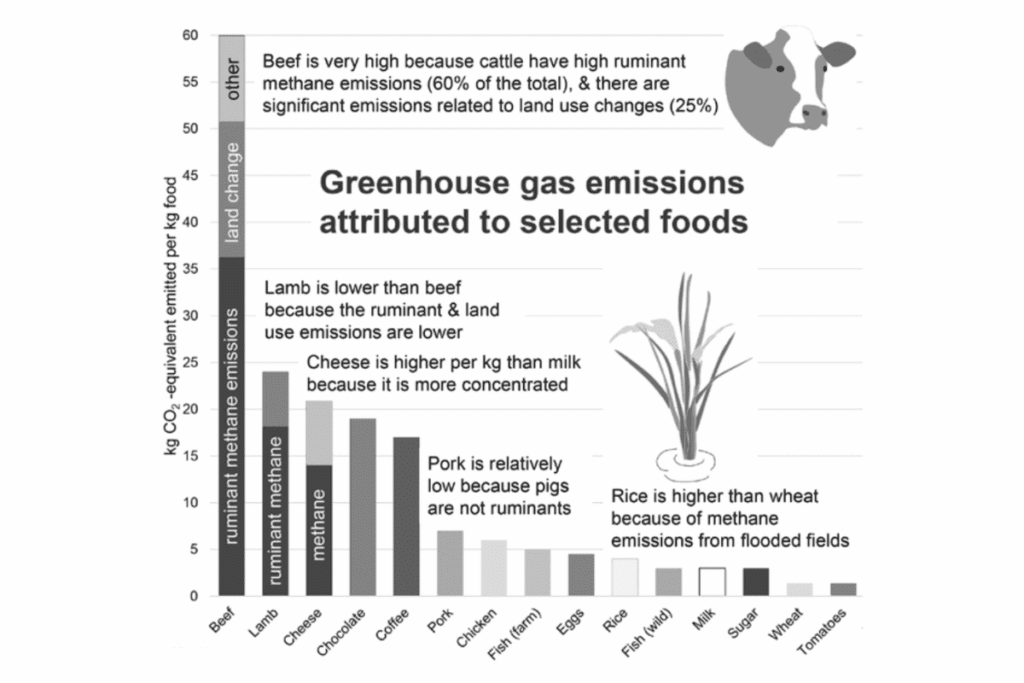

Maybe your diet is part of the problem. As you can see from figure 11.2, a diet that is rich in red meat (especially beef ) adds a lot to your GHG production, more so than any other food choices you make. Reducing your meat intake would immediately reduce your carbon footprint, and your food budget. It would likely make you healthier too. A review study carried out in 2015 shows a strong correlation between beef consumption and negative health outcomes.9 If most of us were to significantly reduce our beef consumption, our GHG emissions would go way down, and it might also be possible to restore the forest on some pasture and grain farmland. That’s because we could grow equivalent amounts of protein embodied in other foods on a small fraction of the land that it takes to produce beef. Over 165 square meters (m2) of land is needed to produce 100 grams of protein as beef, versus 40 m2 for cheese, 27 m2 for milk, 8 m2 for nuts, and 2 m2 for tofu.10 See section 5 of the appendix for an explanation.

The “waste” slice in figure 11.1 represents emissions from both solid waste (landfill waste) and sewage. There isn’t much that individuals can do about their sewage waste (except maybe to eat less!), but we can make a difference with our landfill waste. Remember that the key problem is the emission of CO2 and methane that results from the breakdown of organic matter within landfills. Our main goal needs to be reducing the amount of organic matter that gets placed in a landfill. Some municipalities have compost collection systems in place, so residents of those places must make sure to put their compost into the green bin provided.

In places where such programs don’t exist, residents should do every- thing they can to limit the organic component of their waste. That might start with preparing less food so there is less wasted food on plates and making sure that leftover food gets used. For those that can, it should also mean backyard composting so that the carbon in organic matter can be sequestered in the soil. Those that cannot compost at home might be able to find community composting options in their neighborhood. Food waste is a problem because no matter what we do with it, there will be some GHG emissions. If it is sent to a regular landfill, a significant proportion will be as methane, and that needs to be avoided. At most composting plants, nearly all emissions are as carbon dioxide, not methane.

To sum up, most of the personal changes that we need to make to reduce our climate impacts have positive side effects that will make us physically and mentally healthier and also more comfortable in our homes. They will also have significant other environmental benefits. These may seem like small actions that will have little impact on a big problem, but this is exactly how big things get done. If you set the example, individual actions can snowball through your community.

One other issue, and perhaps it is the most important individual contribution that we can make, is to vote every chance we get. Voter turnout is depressingly low in many places around the world for several reasons, the mostly commonly cited ones being “not interested in politics” and “too busy.” Both stem from a lack of confidence in, or even outright disdain for, political systems and politicians. While that is perfectly understandable, if we want to see changes in how things are done— changes that will lead to a viable climate future—we need to get over it. According to the business magazine Forbes, the main reason Donald Trump won the 2016 US election was because Democrat voters stayed home in droves on election day.12 So, if you care about the future, you need to hold your nose and vote, you need to tell your friends and family that you voted, and you need to let the politicians know that you are voting for the climate (and of course for whatever else you think is important).

| The Public Health Benefits of COVID-19 and of Taking on Climate Change There is no doubt that the COVID-19 pandemic has had, and still has (in mid-2023), enormous health, social, and economic costs, but there have been some surprising beneficial outcomes. Who doesn’t love virtual family gatherings and day-long Zoom meetings? OK, maybe you don’t, but you’ll be glad to hear that there was a significant but temporary reduction in CO2 emissions during the height of the COVID outbreak in 2020, which resulted in small overall reductions in CO2 emissions for the year—a drop of 6.4% from the previous year 3 (see figure 7.4). The decline in the use of fossil-fueled vehicles also led to reduced emissions of other types of pollutants, especially nitrogen oxide and particulate matter. Some benefits of that were clearer views and brighter night skies in many places that are normally quite badly polluted, but there were also significant health benefits. In China the use of private vehicles was strongly curtailed by the government over a period of several months in 2020. That led to a dramatic reduction in vehicle-related emissions including NO2 and particulate matter. Yale University’s Kai Chen and co-authors estimated that the number of deaths avoided because the air was cleaner due to the driving restrictions during that period was just over 12,000, while the number of deaths attributed to COVID during the same period was around 4,300. |