Root vegetables may look humble, but they’re powerhouses in the garden and the kitchen. From carrots and beets to potatoes and lesser-known gems like salsify, these underground crops are packed with nutrients, flavor, and staying power. They store well, grow reliably, and have been feeding people for thousands of years.

In Root Vegetables, the newest book in Jean-Martin Fortier’s Grower’s Guides series, you’ll dig into what makes these crops so special, how to tell the different types apart, and why they deserve a spot in every gardener’s plan—and every cook’s kitchen. This excerpt shows just how much value lies beneath the soil.

Excerpt from Root Vegetables: The Essentials

Vegetables that grow underground—grouped together under the sizable umbrella term “root vegetables,” even though some are not in fact roots—include crops that are essential to our diet and other lesser-known plants with subtle flavors that make them just as precious. They are all treasures of the earth.

Vegetables tend to be classified by botanists and market gardeners according to the part of the plant that they represent, which is generally the part that we eat. For example, we eat the leaves of leafy green vegetables like lettuce and spinach, whereas with fruit vegetables like tomatoes or melons, we consume the fruit. When it comes to root vegetables (which, mind you, are not always true roots!), we eat the parts that grow underground.

All plants have roots, and the root system is essential for plant growth. It acts as an anchor in the soil, allowing the plant to withstand wind and to bear branches and foliage, as well as flowers and fruits. This dense network of roots (each one a different size) can make its way into even the smallest crevices in the soil, allowing the plant to absorb the nutrients (soil minerals) and water needed to develop aboveground organs like stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits.

Not all underground plant organs are edible. Some are unfit for consumption and may even be toxic, so it’s best to get more information before eating them. Others have been identified as edible since the dawn of time, and some of them are especially interesting because they are flavorful, easy to grow, or quite simply, high-yielding. The underground organs of plants known as root vegetables are among these classics.

Botanically speaking, not all underground organs are roots. The catch-all term “root vegetables” refers to all vegetable species with organs that grow underground and at the soil surface. However, the parts of the plant that we eat are not always roots in the true sense of the word. So, we need to distinguish true roots from plant organs that also grow underground or at the soil surface that aren’t actually true roots.

The two vegetables described in this book that are most similar to a true root, i.e., a root that is not a storage organ, are scorzonera (a black root) and salsify (a brownish off-white root sometimes called vegetable oyster). These slender taproots are protected by thick black or brownish skin, with an appearance and flavor that have changed very little over the centuries.

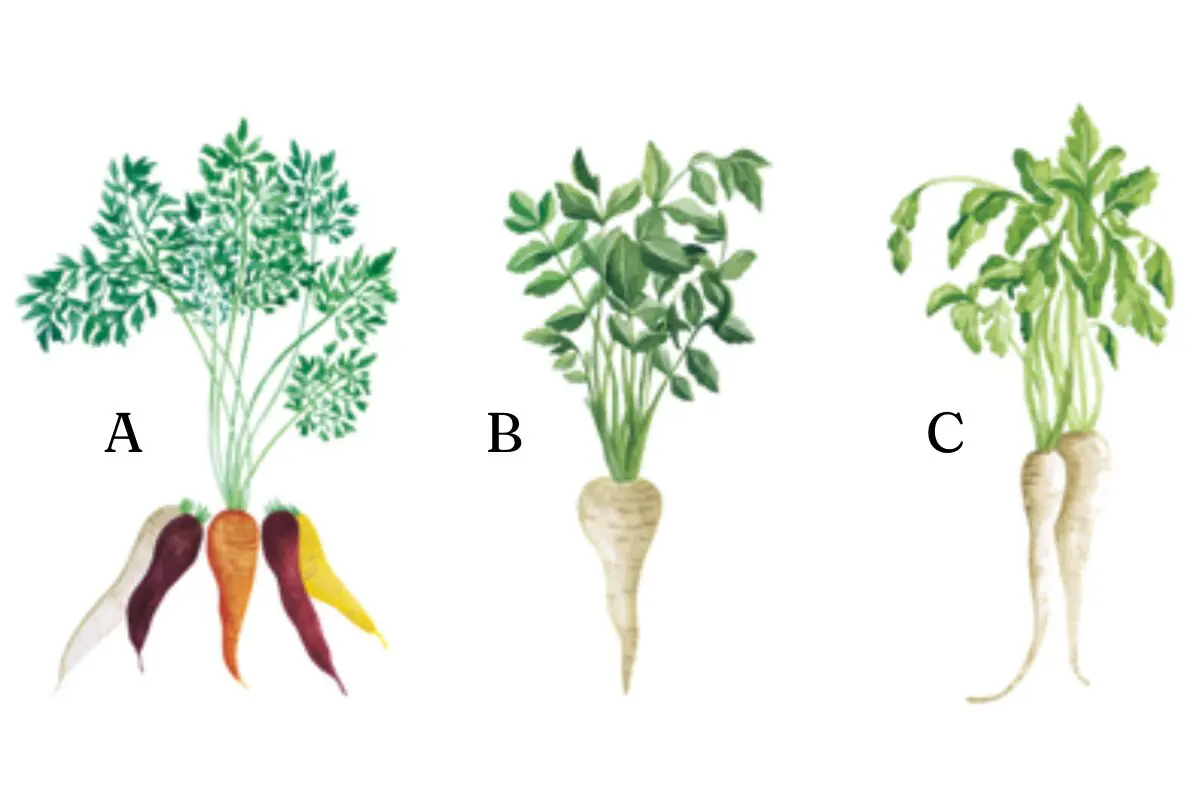

Another category that is quite similar, from a botanical perspective, includes carrots, parsnips, turnip-rooted chervil, and root parsley, which are also known as conical roots or storage roots. These root vegetables can be distinguished from scorzonera and salsify by their slightly thicker and fleshier taproots, which serve as storage organs and can be found underground or partially buried. In the plant world, the process by which taproots become enlarged is referred to as root thickening or storage root formation. This allows the plants to build up nutrient reserves, especially to prepare for hard times ahead, like a cold season in our region. As soon as milder weather returns, they can regrow by drawing upon stored nutrients.

These reserves lend the roots a thicker and fleshier appearance, and when the skin is colored, they look more appetizing. Beyond their physical appearance, storage roots also have an appealing flavor as the reserves are primarily made up of tasty sugars.

The word “tuber” comes from the Latin tuberculum, meaning “small swelling.” In root vegetables, this refers to underground organs that appear enlarged, range in size, and store nutrients with a high starch content. Tubers grow along the roots, which keep them all connected. Unlike the taproots of true roots and storage roots, when dormant, tubers have all the necessary organs to develop a new plant if separated from the mother plant. Thus, each tuber is capable of producing roots, stems, leaves, and flowers that would allow it to be self-sufficient and, most importantly, to develop a plant identical to the one it originated from. Oca, mashua, sweet potatoes, potatoes, and yacon produce tubers with good flavor, high yields, and a long shelf life, which have made them some of the world’s leading root vegetables.

Rhizomes, often found in flowering perennials like irises or shrubs like bamboo, are underground organs that grow horizontally. Helianthus strumosus (paleleaf woodland sunflower) and Jerusalem artichokes are two that have an edible rhizome, so they are considered to be vegetables. In fact, they are quite often listed as both perennial vegetables and perennial decorative plants, grown for their flowers or foliage. Botanically speaking, rhizomes are underground stems. They are cylindrical, range in thickness, and have a dented surface that features rough dark skin, in general, quite similar to roots (for which they may be mistaken). However, rhizomes can be distinguished from roots by the fact that they have buds and small roots that allow them to grow new stems, leaves, and flowers every year. Such plants are therefore perennial and independent organs that, if cut into fragments, may continue growing and produce a new plant. This can make them a little invasive, especially if they are not killed off by frost.

The last category of root vegetables is not in fact a root since the edible organ, the hypocotyl, grows at the soil surface, well above the root system. It sits between the base of a plant, called the crown (where the root and shoot systems meet), and the cotyledons (the first 2 leaves to appear during germination). This category has the largest number of root vegetables: beets, kohlrabi, celeriac, turnips, rutabagas, and radishes, including daikon radishes. The flesh of these root vegetables, although protected by a layer of skin, is more exposed to light as the storage organ grows aboveground. These crops should be covered with soil through regular hilling to prevent cracking and hardening.

Note: Bulb-producing vegetables like garlic, onions, and shallots are a separate category from root vegetables because the underground organ consists of leaves compressed into densely packed scales around a vegetative growing point. Edible bulbs used in vegetable gardens will be the subject of a specific book in this collection.

Root vegetables are mainly intended for human consumption, but some species are cultivated specifically for livestock. These are known as fodder roots or forage roots. You might, understandably, wonder why we eat these underground organs that don’t look particularly appetizing at first glance. Some of them, like turnip-rooted chervil, root parsley, Jerusalem artichokes, and salsify, could have remained a marginal part of our diets, or even been forgotten—and they were, for a while—but they are making a comeback, showcased and celebrated by creative chefs. So how did root vegetables come to be so successful? It is likely due to their origins.

Humans have probably been eating underground plant organs since the Neanderthal period. When analyzing the teeth of Neanderthals, researchers found both plant matter and tuber residue. Later, in European prehistory down through the Middle Ages, the harvest and consumption of edible roots from wild plants—initially gathered in nature and later domesticated and cultivated—were common practices. Don’t forget that the variety of vegetables we know today did not exist then. Most fruiting vegetables, such as tomatoes or eggplants, which were brought to Europe from South America in the 17th century, were not yet a part of daily diets. People simply gathered and ate leaves, wild fruits, and roots. Since roots were relatively fibrous, offered little sustenance, and had poor flavor, we can speculate that they were primarily used to provide a little variety and perhaps some beneficial nutrients.

Root vegetable cultivation continued and developed further most likely due to improvements made to these crops over the centuries. Unlike leafy vegetables, characterized by their freshness and appetizing colors, most root crops probably looked unenticing (filiform organs, encased in rough, cracked, and dark skin—you really had to be hungry to eat them!). But they kept well and could therefore be consumed long after harvesting, when they were far from fresh. And thus, they became the staple of many diets, for centuries, and especially in times of famine and war, as they were easy and inexpensive to cultivate.

It was only much later, starting in the 17th century, and then in the 18th and 19th centuries, that the roots increased in color, flavor, and yields, thanks to crossbreeding with species that came from other continents in the luggage of traveling botanists. Carrots are the best example of this change. Originally, wild carrots were white, purple, and red, but not orange. Orange varieties first appeared in the 17th century when they were created by Dutch seed producers looking to pay tribute to the House of Orange-Nassau, a family that ruled the United Provinces, known today as the Netherlands. To achieve this, they crossed red wild species with yellow wild species from the East. Over the centuries, improvements in root vegetables multiplied, and even today, seed farmers are constantly improving and perfecting these underground plant organs, elevating them to the status of treasures of the earth.