Movies and social media often prioritize gossip and quick exchanges over genuine dialogue, which can distort our perception of real-life communication. Misunderstandings arise when assumptions replace clear, honest conversations. Non-verbal cues, like body language, convey nuanced messages swiftly and instinctively, yet our unique experiences can hinder understanding others’ perspectives.

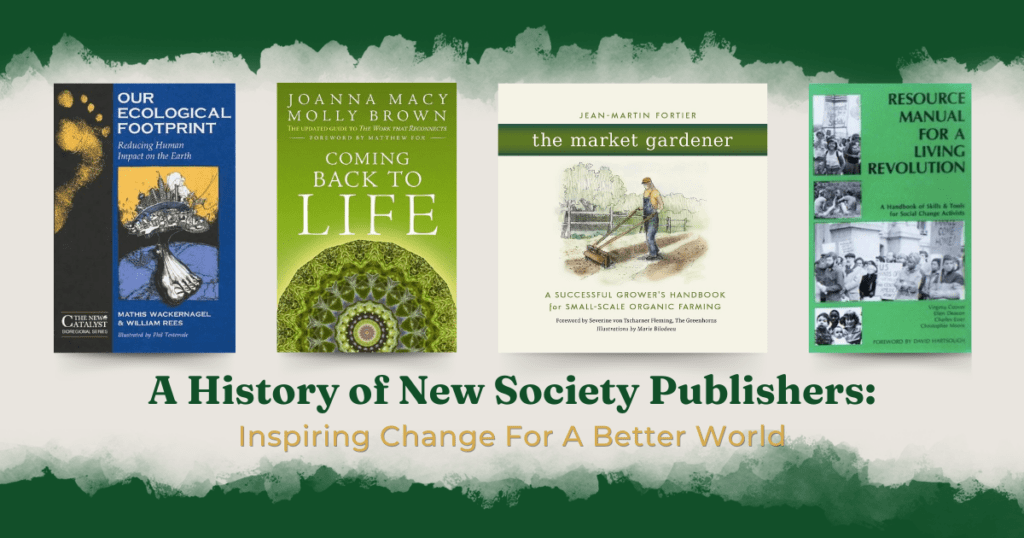

In this excerpt from Are We Done Fighting? author Matthew Legge teaches us that to foster mutual understanding and master nonviolent communication, we must merge diverse viewpoints through meaningful conversations, actively listening, reflecting, and striving for clarity to bridge perspectives and cultivate genuine understanding.

From Chapter 8: Communication

Have you ever been ready to launch into a heated argument only to find the other person unexpectedly pleasant? As much as you try to hold on to it, that righteous momentum can just slip away. It’s very demanding to keep up a “belligerent approach that’s not reciprocated.” This is one of the best ways to shift to a healthier conversation, and it’s often done with humor. When we laugh together we feel closer, diffusing tension, even deflating our exaggerated sense of importance. But when it’s directed at people to isolate or belittle them, trivializing real concerns and needs, humor becomes power-over. It seems to come very easily to us to give orders like “Get a sense of humor” if people don’t laugh at our demeaning joke, but feelings don’t tend to work that way—changing on external command—so this communication style usually won’t help. Instead, a useful approach is “humor but not humiliation”—make jokes to poke fun at situations, not to alienate people.

Psychologist Marshall Rosenberg spent his career studying and developing ways to communicate effectively. He called the results nonviolent communication. Rosenberg suggested that most of us are using language in confusing ways, often while trying to get others to do what we want. Yet most of us also like to feel in control and to resist orders, so we feel resentful of so many people telling us what to do. Our demands are a good way to get pushback. (Signs at a hotel pool saying, “Don’t You Dare Litter” caused increased littering.)

Even if we tell someone in a friendly way what they should do and they comply, they likely aren’t acting out of joy or response to their own needs. They might feel put upon. We get what we want in the short term, but strained relationships and bitterness could follow. Statements like “You should…” express the isolated and abstract ideas of power-over. We’re describing an outside standard, a judgment not necessarily connected to what’s happening right now.

To bring the focus back to the moment, we can use a discovery made by many religions and philosophers and more recently used in therapies like cognitive behavioral therapy: no one is causing our feelings. When we say, “You’re making me angry,” we’re using a convenient shorthand, but it’s not quite accurate. Of course others provide stimuli, but we weave these together and generate our feelings. We all know this is true because the same events don’t always make us feel the same way, and they certainly don’t make everyone around us feel the same. If someone cuts us off in traffic one day we might feel a violent rage, another day just a mild annoyance, another a sense of relief that we’ve been reminded to slow down and not rush the way this person is.

The stimulus—what others do or communicate—is not in our control, but we are very much sculpting our experiences, even if they seem automatic. “An emotion is your brain’s creation of what your bodily sensations mean, in relation to what is going on around you in the world,” neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett contends. We’ve already seen examples of this—when we touch a hot cup, then shake hands with an interview candidate, our brains interpret that to mean that we feel warmly toward that person. When we smell some garbage and are asked how immoral it is to lie on our resume, we interpret the sensation of disgust in our body as relating not to the smell, but to the immorality of lying. “Emotions are not reactions to the world. You are not a passive receiver of sensory input but an active constructor of your emotions.”

We might know we’re having an unpleasant feeling about being cut off in traffic, but there are countless concepts we might use to describe our feeling to ourselves. Studies have shown that folks who are able to distinguish between their feelings more precisely, using larger and more refined vocabularies to label and understand their emotions, are more flexible in regulating their emotions, deal with stress better, and are less aggressive when someone hurts them.16 This realization can liberate us to communicate in richer ways. We might stop looking to external standards and judgments about what’s happening and start speaking more accurately and precisely for ourselves. We could try stating only what actually occurred and how we’re feeling, keeping the responsibility for our feeling with us. This frees us too from the impossible burden of trying to make other people happy. Since we don’t generate emotions in anyone else, all we can do is act well, not cause someone else to respond how we might like. Once we’re attending to and communicating our own feelings, we then begin to discover and express our needs.

| For more information on the topic of nonviolent communication, please visit our Nonviolent Communication page. |