For decades, we’ve been told to fear fat — and fill up on grains instead. But what if that advice got it backwards?

In this excerpt from Feed Us With Trees, author Elspeth Hay unpacks the shifting science and cultural narratives behind America’s modern diet. With warmth and curiosity, she explores how generations of families — including her own — were shaped by low-fat guidelines, and what current research reveals about the real culprits behind chronic disease.

From government food pyramids to tree nuts and insulin, Hay invites readers to rethink what truly nourishes us — and why it might be time to bring fat, and flavor, back to the table.

Excerpted from Chapter 10: Nuts in the Kitchen

Our modern diet is problematic. On this much, at least, everyone has agreed for some time. But the specific connection between diet and disease has for decades been a topic of heated debate. In the early 1900s, the problem, as indicated by Atwater, was believed to be simply an “imbalance.” The conventional wisdom since the 1860s had been that this imbalance lay on the side of carbohydrates: We were eating too many starchy foods like grains, sugar, and potatoes, and as a result we were getting fat and sick. But in the decades since my grandmother first began cooking for her family in the 1940s, dietary advice in the United States has undergone a tectonic shift. By the time my mother had a family of her own, the darlings of my grandmother’s recipe notebook — the walnuts baked with Worcestershire sauce and butter, the deviled eggs, and the pimento cheese dip (a delightful Southern dip made mostly of shredded cheddar, cream cheese, and mayonnaise) — were suddenly considered dangerous. “The diet of the American people has become increasingly rich,” Dr. David Mark Hegsted, Professor of Nutrition at the Harvard School of Public Health, wrote in the first ever USDA report outlining “Dietary Goals for the United States,” published in February 1977, just a few months before my parents’ wedding. We were eating too much fat and cholesterol, he told the nation (as well as too much alcohol, salt, and sugar, though this part of the message went largely unheard), and it was time to cut back to save our hearts, waistlines, and general well-being. The best way to do this, the report suggested, was to replace high-fat foods with lower-calorie carbohydrates.

Thus began the low-fat era. Thanks to my loving and well-intentioned mother, when I was born in 1985, the milk in our house was skim and the cheddar was low fat. Our fridge was stocked with an imitation mayonnaise called “Vegenaise,” supposed to be heart healthy because the high-fat and high-cholesterol eggs were removed, and my mother subscribed to Cooking Light, a magazine devoted to taking favorite recipes and removing as much as possible of the original salt, fat, and cholesterol. We studied the USDA food pyramid in school, which taught us to prioritize carbohydrates — six to eleven servings of bread, cereal, rice, or pasta every day — alongside three to five servings of vegetables, two to four servings of fruits, two to three servings of milk, yogurt, or cheese, and two to three servings (total, not each) of meat, poultry, fish, dry beans, nuts, or eggs. As I got older, I found the advice on nuts particularly confusing, since there was also a special category at the very top of the pyramid for oils, sweets, and fats (“naturally occurring and added”) that came with an ominous all-caps warning: “USE SPARINGLY.” Most nuts, of course, are fatty. And unlike the low-fat cheeses, yogurts, and skim milks my parents and so many of my peers’ families stocked our refrigerators with, nuts evidently did not come in a “low-fat” variety. My dad ate a small bowl of peanuts every night as a snack before dinner, but my dad also grew up in France, had the metabolism of a horse, and frequently made my sister and me liverwurst-butter sandwiches. Clearly, he lived in off-pyramid territory.

Sometime in the 1990s, the USDA revised its advice slightly and announced that actually, not all fats were bad. There were “good fats” and “bad fats,” nutrition researchers clarified belatedly, and nuts — along with other foods high in unsaturated fat such as olive oil, avocados, peanut butter, fatty fish, and vegetable oils — were “good.” Still, every gram of fat has nine calories, authorities warned, while every gram of carbohydrate and protein has only four. A little bit of fat might be healthy, but it was best not to eat too much if you wanted to stay slim and healthy.

As time went on, the advice kept changing. By the time I graduated from college in 2007 and began grocery shopping for myself, the entire “lipid hypothesis” — the idea that the fat we eat clogs our arteries and gives us heart disease — was being challenged. “What if It’s All Been a Big Fat Lie?” journalist Gary Taubes asked in a 2002 New York Times article, laying the groundwork for skeptics to examine a growing body of evidence that in fact, fats might not be so bad. For the health-conscious eaters of America, the decades between 1970 and the present have been, to put it mildly, a confusing time.

Reflecting on this history as I made my way up from the kitchen to my desk, I realized that I wasn’t sure what sort of health authority I might trust on the subject of swapping nuts for grains. Not the federal government, to be sure, which is still pushing outdated low-fat recommendations from the 1980s. And not the American Heart Association (AHA), which I’d recently learned was essentially launched into the mainstream conversation on heart health in 1948 with a generous donation from Procter and Gamble — a company that had quite a bit to gain from convincing the public to swap traditional fats like butter and lard for its own new-fangled Crisco and canola oil.

I’d recently read an article detailing the AHA’s present-day ties to the pharmaceutical industry, in which physician and medical professor Barbara Roberts and investigative reporter Martha Rosenberg had called both the AHA and the American College of Cardiology “an egregious example of much that is wrong with medicine today.” So, none of these authorities. But a glance at my bookshelf reminded me that there was someone I do trust when it comes to nutrition advice — food writer Nina Planck, whose 2006 book Real Food: What to Eat and Why garnered widespread attention for presenting what one reviewer called “a convincing alternative to the prevailing dietary guidelines, even those treated as gospel.” Planck’s book was where I’d learned to be skeptical of mainstream dietary suggestions in the first place, and she was one of the first authors to help me connect the dots between whole foods and healthy eating. Standing by the bookcase as I flipped through my dog-eared copy, I wondered if perhaps she’d be willing to talk with me about the potential health consequences of swapping grains for nuts.

When I emailed, she responded quickly. “I’d love to,” she said. “Nuts are the best.” We scheduled a call for the next day.

In the meantime, I spent the afternoon brushing up on the two chapters of her book I remember being most captivated by: “Real Fats” and “Beyond Cholesterol,” about the causes of heart disease. The “cholesterol theory” of heart disease, Planck argues in these chapters, promotes the idea that eating fatty foods raises our blood cholesterol, which in turn makes us unhealthy. But “the truth,” she writes, “is more complicated.”

To talk about the potential health implications of replacing some or all of the foundation grains in our current diet with nuts, Planck told me when we got on the phone the next morning, first we needed to get a better understanding of our old dietary villain: fat. “I like to remind people” that healthy people “eat breakfast, they eat dark chocolate, and they eat nuts,” Planck said when I asked her about the long-rumored connection between eating more nuts and lowering our chance of developing chronic diseases like heart disease, diabetes, and obesity. Despite what our government’s been telling us for decades, she went on, a growing pile of evidence suggests that it’s modern, industrialized foods — particularly refined flours and sugars — that are responsible for our major killers, not the traditional fatty foods we’ve villainized. I nodded; I’ve been following the international debate on fats and heart health for decades, and I’d recently rewatched a 2017 speech by leading Canadian cardiologist and former president of the World Heart Federation Salim Yusuf. Yusuf spoke in Switzerland at a meeting of cardiologists from around the world, and for the last fourteen years, he said, he’d been part of a group conducting a large epidemiological study on diet and heart disease. When the results began to come in, “We were in for a big surprise. We found that increasing fats was protective,” he told the crowd, “and that once you get past about…55 percent of carbohydrate intake as percent energy, there’s a steep increase in the risk of cardiovascular disease.”

Why? I wondered.

Well, as Planck helped me understand, heart health and metabolic health are intricately connected. Americans tend to talk about heart health like it’s a special category, separate from other diseases, but in fact, although having a heart attack might be the thing that kills you, it’s actually the end stage of a progressive metabolic disease. It’s not an accident that the diet-related diseases so many Americans struggle with — obesity, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and high blood pressure — tend to be experienced together. They are all symptoms of the same metabolic problem. When it comes to fat and cholesterol in our diets and disease, Planck explained to me, the big thing we need to understand is a hormone called insulin. Insulin is produced by the pancreas to regulate our body’s supply of energy. When our blood sugar gets too low, we feel faint; when it gets too high, we suffer serious health problems affecting our heart, kidneys, nervous tissues, and eyes. If blood glucose gets really high, this condition can become life threatening — we go into a diabetic coma. This is why type 1 diabetics, whose bodies are unable to produce insulin, must inject it — without this essential hormone, they cannot use food for energy, and they die. Insulin’s job is to keep our blood sugar as even as possible by sending glucose out to be used when we need it, and by helping to store it when we have too much. When we mess with our body’s careful regulation of insulin production and blood sugar control, Planck told me, “we wreak havoc on our metabolic systems.”

The best way to avoid this is to eat fat, protein, and fiber along with our carbohydrates. When we rely heavily on refined carbohydrates for energy — think refined grains, sweeteners, and juices — we send our blood glucose levels through the roof, and our pancreas tries to respond accordingly, working overtime to pump out huge amounts of insulin. At first, our cells try to respond to all this insulin, but eventually — if we do this meal after meal — they get overwhelmed. Imagine a family where the parents yell a lot. At first, the kids might listen and try to make behavior changes, but eventually, they learn to tune all the yelling out and simply stop listening. This is type 2 diabetes, Planck has written: “the cells are deaf to insulin.”

As a result, the more refined and low-fiber carbohydrates we eat — and the less fat and protein we eat with them — the more likely we are to develop what’s called insulin resistance or metabolic syndrome: the first step on the road that, if we keep on heading down it, eventually leads to type 2 diabetes, obesity, and heart disease. Today, dysregulation of insulin — not the amount of fat or cholesterol in our diets — is increasingly recognized as the biggest single risk factor for our number one killer: cardiovascular disease. “High blood sugar, fat around the abdominal area, high triglycerides, high circulating LDL, damaged cholesterol” — all of these are symptoms of metabolic disorder, Planck explained to me, not its cause — a statement that other researchers echo. LDL (low-density lipoprotein), for instance, is a repair molecule — it helps repair damaged arteries. Blaming its presence in the bloodstream for a heart attack, Planck has written, is like seeing firefighters at a burning building and deciding they’re the cause. The same goes for getting fat and eating fat. All of which, I thought that afternoon, snacking on a handful of my grandmother’s Yummy Nuts, put the USDA pyramid I grew up with in a new light. “There’s a wonderful and shocking poster from the pig industry that shows the food pyramid for fattening hogs,” Planck told me just before we said goodbye. “And it looks exactly like the USDA food pyramid.” Grains at the bottom, and fatty foods — nuts included — at the top.

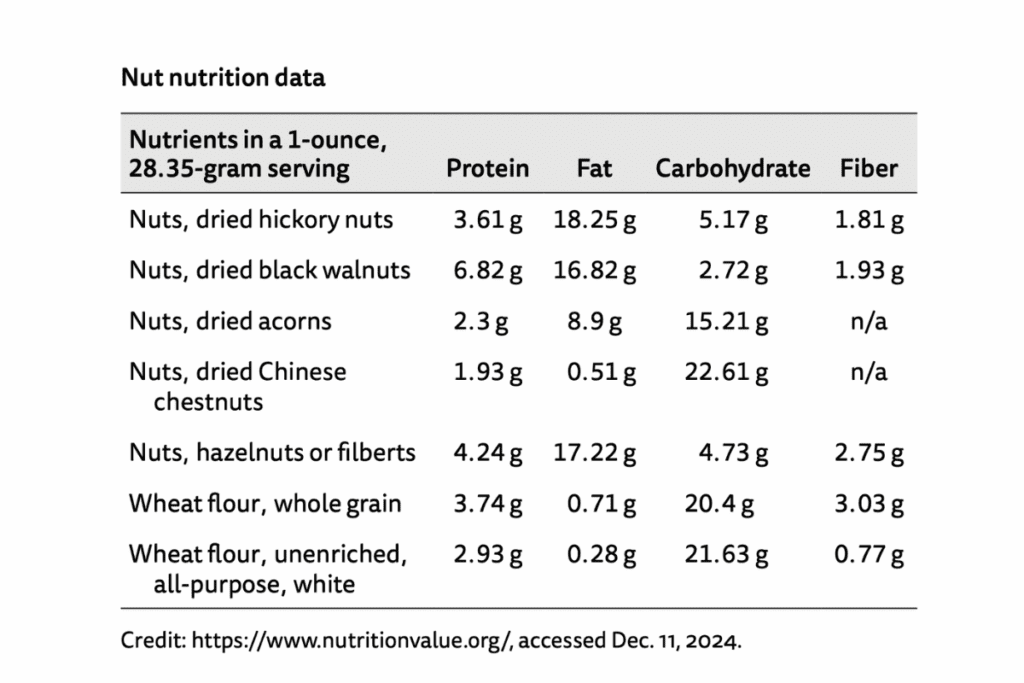

Nuts, of course, are a varied bunch. Some tree nuts, like certain acorns and all chestnuts, are primarily carbohydrates; others contain significantly more fat. When I went online after talking to Planck to try to compare macronutrient contents for several species of tree nuts — and to look at them in comparison to common grains — I found that the compositions of the various nuts were quite different. For instance, a one-ounce serving of chestnuts is reported to contain a mere 0.51 grams of fat; acorns (the data don’t specify from what species of oak) contain 8.9 grams of fat; and hazelnuts, black walnuts, and hickory nuts have much more fat — 17.22 grams, 16.82 grams, and 18.25 grams, respectively. When it comes to carbohydrates, the situation is flipped. Chestnuts have the most, with 22.61 grams, followed by acorns with 15.21 grams, hickory nuts with 5.17 grams, and black walnuts with 2.72 grams. None of the nuts have particularly huge amounts of protein, with most hovering between two and four grams, and most have respectable but not particularly high amounts of fiber.

For grains, the situation is reversed. When we eat them in their whole-grain form, they’re almost all excellent sources of fiber — which, remember, helps prevent metabolic disease. But grains don’t provide much fat or protein, and when we eat the refined versions — which we usually do — they have the glucose-slowing fiber taken out. Perhaps the problem wasn’t grains in and of themselves, I thought as I read, but the way we are preparing them and the quantities in which we are eating the refined varieties. One alarming chart published in the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans informed me that the top source of calories for the average American as of a decade earlier was “grain-based desserts,” with “yeast breads” (that I was willing to bet my left arm were made mostly from white flour) ranking second. Certainly, substituting nuts — any of them! — for these foods would improve the health of the average American.

In fact, the more I thought about how it might change our health if we were to replace the grains in our diet with nuts like acorns, the more I realized that our government has already forced at least one population into the sorry reverse of this experiment. “Until quite recently, as in maybe the last three generations, acorns provided almost fifty percent of [Karuk] people’s total calories,” Kari Marie Norgaard had told me when I’d first called her in the spring of 2020. Rations provided to Indigenous Peoples by the federal government are notoriously high in refined grains and sugars and have been since the government first began delivering them to some tribal communities nearly two centuries ago. In many ways, the foods long ago dumped on Indigenous communities reflect the state of the American diet in general today.