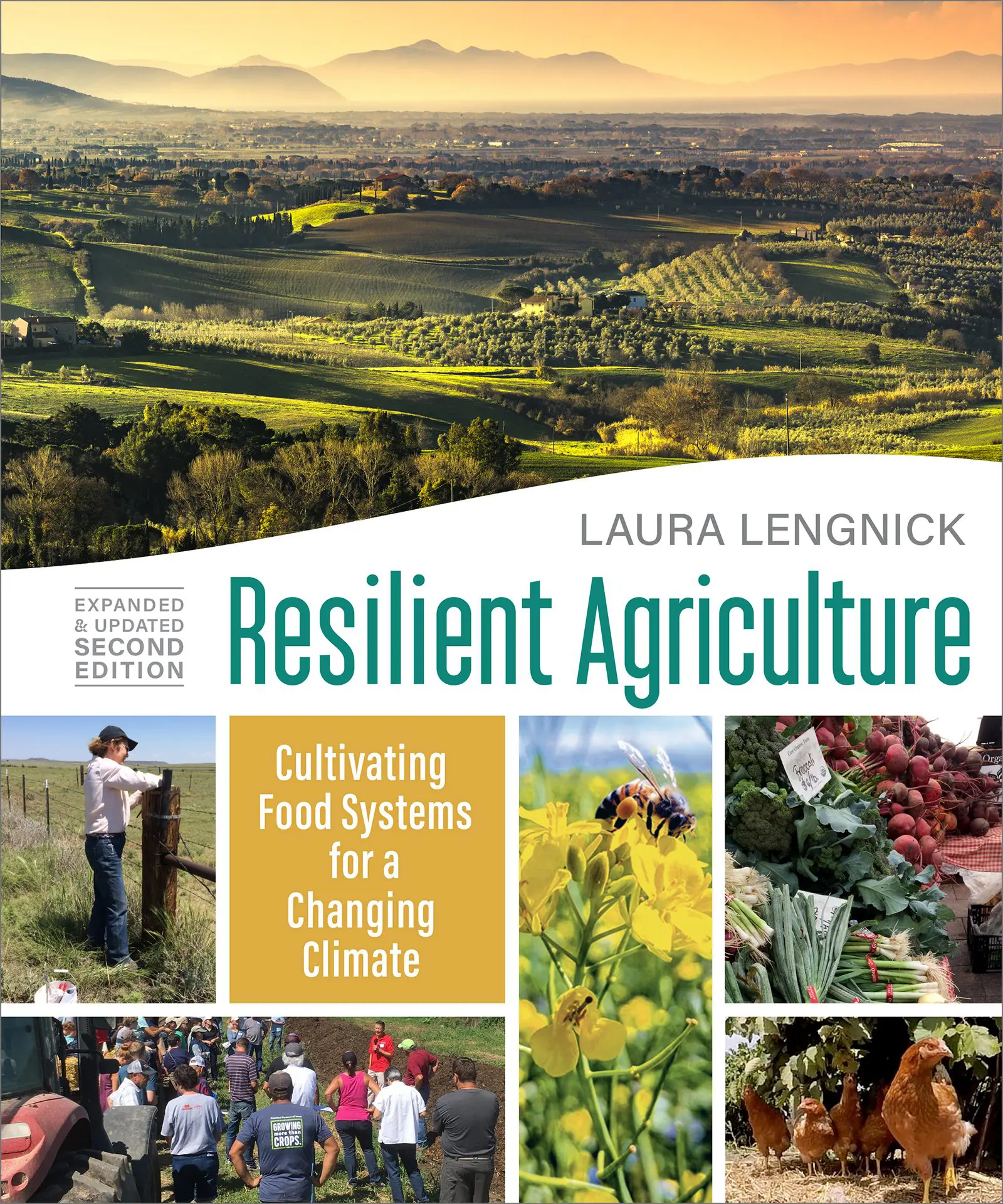

Resilient agriculture is more than just a buzzword—it’s a vital strategy for ensuring our food systems can handle the challenges of a changing climate. In Resilient Agriculture, Second Edition, author Laura Lengnick dives into the latest science on climate risk and resilience by sharing the inspiring stories of award-winning farmers and ranchers. These stories showcase how agriculture and food systems can do more than recover from setbacks; they can actually strengthen the natural, human, and social resources that keep us going.

In this excerpt, Laura describes moving away from a traditional “bounce-back” approach of agriculture to a broader, more innovative view rooted in social-ecological resilience. This approach focuses on three key capacities: protecting the system from harmful changes, recovering from those changes; and—perhaps most importantly—transitioning to a new, more resilient system when needed. Resilient agriculture doesn’t just help our food systems survive; it ensures they can thrive, even in an unpredictable future.

More Than Bouncing Back

Social-ecological resilience thinking can help us go beyond the old “bounce back” idea used by engineers and dig deeper into the full range of options available for cultivating resilience in food and farming. The resilience of living systems is determined by three complementary capacities that work in different ways to sustain the system over time by protecting the system from damaging change, recovering from damage caused by change (the bounce back) and transitioning the system to a new identity when necessary or desired (the bounce forward). Resilient systems tend to cultivate all three capacities.

- Response capacity is the ability to respond to disturbances and shocks—both those that are anticipated and those that are not—in ways that avoid or reduce damage and to pivot swiftly to take advantage of new opportunities. Practices that enhance response capacity involve cultivating system relationships that can eliminate damages associated with disturbances, so there is never a need to bounce back. When there is damage, rather than “bouncing back” to an outdated twentieth century standard, we can instead make investments that improve response capacity.

- Recovery capacity is the ability to return to normal function swiftly and at low cost in the event of a damaging disturbance. This idea of “bouncing back” is usually what people mean when they talk about resilience. While bouncing back from damage is important, relying on recovery capacity to sustain a system as conditions change tends to become more costly and less effective over time.

- Transformation capacity is the ability of the system to make fundamental changes in order to enhance response and recovery capacity as conditions change. Managing for transformation capacity is uniquely valuable as we wake up to the need to transform agriculture and food systems.

Once you know about these three complementary capacities, you can begin to appreciate just how limited the old “bounce back” thinking is. Social-ecological resilience thinking opens up a whole new world of possibility perfectly suited to the practical realities of managing our businesses and communities to thrive in changing conditions. Let’s take a closer look at how some sustainable producers in the U.S. cultivate response, recovery and transformation capacity on their farms and ranches.

Response

Agricultural practices that promote response capacity increase the ability of the farm or ranch to continue to function across a wide range of conditions. These practices include relatively simple adjustments to the production system such as replacing an existing crop variety with a more robust variety, adding mulch to conserve soil moisture and reduce soil temperatures, or adding field irrigation or drainage systems. More complex adjustments involve diversifying the existing crop production system by increasing the biodiversity of the system, for example by adding cover crops, new annual or perennial crop species, or livestock. Adjustments that enhance the response capacity of a farm or ranch can also be made in non-crop production areas, for example by restoring wetlands and riparian areas.

These kinds of diversification practices are important to help maintain production in more variable weather and more frequent and intense weather extremes. These practices achieve these aims by assuring the supply of critical resources needed for crop growth and development, or by spreading production risks through the season by including crops that differ in their sensitivity to specific weather-related disturbances. Diversification can also reduce production costs, because the biodiversity in the system can promote ecosystem services that reduce or eliminate the need for inputs such as fertilizers, pesticides and irrigation. Ecosystem restoration can reduce soil erosion and flooding both on the farm and in communities downstream.

Along with using targeted practices to manage specific known risks, cultivating response capacity can also involve using practices that enhance the general resilience of the cropping system by reducing the risk of damage from unexpected disturbances and shocks. For example, many farmers and ranchers who operate highly diversified systems appreciate the flexibility that biodiversity gives them when it comes time to make management decisions based on actual or projected weather conditions.

Gabe Brown uses practices like dynamic crop rotation and cover crop cocktails to enhance the resilience of his operations to more variable weather and extremes. Planting a diverse mix of crops throughout the growing season gives him the ability to fine-tune his crop rotation plan to adjust to current weather conditions. “That’s the beauty of the diverse system of ours,” Brown explains, “At times, we want to plant the cover crop and then if the weather conditions change, maybe it’s dry, we’ll change the mix of species a bit for species that can handle drier conditions, or vice versa. It just makes management so much easier.”

C. Bernard Obie says heavy clay soils make the production risks created by heavy rainfalls particularly difficult to manage at Abanitu Organics. “A heavy rain presents an issue with getting into the field to work,” says Obie. “The soils just don’t dry out quickly and there is a tendency for plants to be stunted or even killed in low-lying areas because moisture sticks around so long in our soils.” Obie built a set of raised beds to improve his ability to adapt to wet soil conditions. “In a year where there’s a lot of rain and it’s early and the temps are cold, the raised beds give us some additional options,” says Obie. He also notes that the challenge of farming in clay is a good example of the “give and take” of farming, because although clay soils are slow to dry out, they also provide some welcome drought tolerance.

Crop and livestock diversification go hand in hand with product and marketing diversification, which adds another dimension to response capacity. Spreading marketing risk among different types of markets— such as direct sales to consumers at farmers markets and direct wholesale to custom food processors and restaurants—can buffer an operation against shocks.

Focusing on producing high-value products or selling into high-value markets can also reduce risk and increase profitability. Because high-value direct and direct-wholesale markets often welcome uncommon and value-added products, they present a financial incentive for diversifying crop production. In addition, these kinds of markets offer producers the opportunity to use robust crop cultivars and livestock breeds that may not meet commodity market standards, but are well-suited to regional growing conditions.

Recovery

Holding some critical resources in reserve in case of damage is key to enhancing the recovery capacity of agroecosystems. Recovery reserves can be natural (storing extra water and feed supplies), human (experience and ease of managing loss and change), social (community memory, knowledge, skills, public assistance), financial (insurance and disaster payments, savings, access to capital) or physical (backup and alternative energy sources, storage, shelf-stable products). Resilient farms and ranches accumulate reserves across the full range of resources under management.

Jim Koan appreciates the way that recent weather challenges have forced him to think outside the box, anticipate what could go wrong and plan for the worst. The Flushing, Michigan, apple grower began on-farm production of hard cider—JK Scrumpy’s—in part to enhance the recovery capacity of his operation. By processing a portion of his apples into hard cider in years when yields are high, he has a nonperishable product he can sell in years when weather disrupts production. This helps him maintain his cash flow. “In 2012, we had only had ten percent of our apple crop. I had half a million dollars invested in those apples,” Koan said. “That was not as big an issue for me as it would have been if we hadn’t had JK Scrumpy’s. I can walk away comfortably saying that I actually made a profit in 2012.”

In August of 2007 we got hit really hard with some really weird flooding caused by 18 inches of rain in a less than a 24-hour period,” Wisconsin vegetable farmer Richard DeWilde recalls. “A lot of crops were peaking just then, like tomatoes. We had pretty big losses because a lot of our farmland is along the Bad Ax River. They called that a thousand-year event. And then we had another one nine months later. That was when I said, ‘There’s no such thing as normal anymore.’ Not many people understand that vegetable farmers have little to no insurance against weather. We can participate in the USDA’s NAP program and we do. N-A-P is the abbreviation for Noninsured Agricultural Production. Noninsured meaning it’s not corn, soybeans, cotton, wheat. It’s not a commodity. NAP is a poor program. It’s totally inadequate and we really don’t have much else. But if you’re a corn farmer, you can buy government-supported, 90-percent-guaranteed income on the corn crop. It’s gross. We should care more about feeding people than raising corn for export and ethanol and corn syrup.

Transformation

Ultimately, the resilience of an agricultural business depends on taking a long view of the operation as a whole. What kinds of more fundamental changes in production system practices, enterprises and markets might be made to enhance the overall resilience of the business now and to prepare for the future? Examples of transformative changes that enhance resilience to more variable weather and extremes could involve shifting from monoculture to diversified crop production or from annual to perennial crops, transitioning from housed to pasture-based livestock production or extending farm operations to include value-added processing.

Tom Trantham’s pasture-based dairy system boasts many resilient characteristics, but it was not always that way. Like many American farmers feeling the pain of consolidation in the agricultural sector during the 1980s, Trantham was producing a lot of milk in a conventional operation but barely turning a profit. “I went through some really rough times in those days. We all did,” he recalled. Although he had long been among the top milk producers in his state, rising feed and farm chemical costs, and falling prices left him with few options when he was refused an operating loan in 1987. After some research into intensive grazing practices, he successfully guided the transition of his 90-cow dairy from feed-based to the forage-based production system he continues to use today. He has dramatically lowered his costs while increasing herd health, milk quality and soil quality. With the opening of the Happy Cow Creamery in 2002, Trantham’s transformation from commodity dairyman to specialty milk retailer was complete. Whole milk, chocolate milk, buttermilk and eggnog are processed on-farm and sold into regional direct-wholesale markets and at an on-farm store that also sells a diverse line of mostly locally sourced fresh and processed products including vegetables, fruits, butter, cheeses and meats.

Colorado fruit grower Steve Ela credits a shift to direct marketing strategies as the reason he has remained in business in a region that has lost 75 percent of its fruit growers over the last 20 years. His family farm was on the same downward path when he took over management in 1990. With declining profits taking a toll on family finances, he looked to direct marketing to turn the farm around. “We started making changes because of bad economics and now we direct market 100 percent of our fruit,” Ela said. “We’ve completely changed our business model in 12 years. Fortunately it’s worked, we’re still here.” Direct markets have also opened up new opportunities for him to diversify crops, because his customers are willing, even eager, to try something new.

A good time to consider transformative changes such as those made by Trantham and Ela is when it looks like the costs—ecological, social or economic—of maintaining the current production system are growing unacceptably high, the performance of the production system begins to consistently fall short of meeting goals or it becomes clear that change is inevitable because of growing environmental, social or economic challenges.

For more information about the resilience of agriculture, check out the interview with Laura Lengnick on Medium.