Planning is at the heart of sustainable farming — not just for crops, but for people, too. In this excerpt from Sustainable Market Farming, Second Edition by Pam Dawling, we step inside Twin Oaks Community, where the goal is to grow fresh, organic food year-round while preserving rest and balance. With 16 key factors to guide the process, Dawling shares how thoughtful, cyclical planning can support both abundance and sustainability through every season.

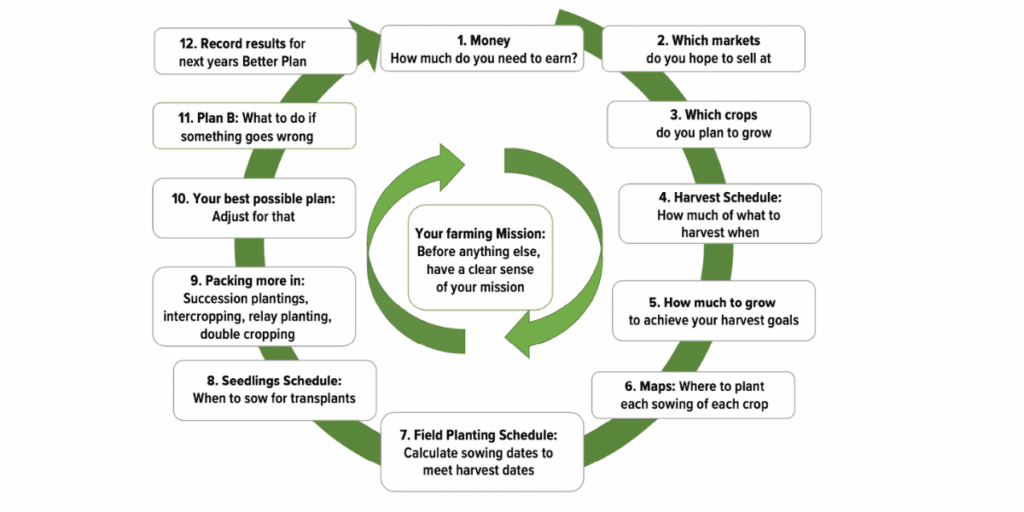

Food production requires planning, and the steps of a good planning process are cyclical, with information from each stage suggesting changes at other stages. Before the cycle even starts, it is important to be clear about the goals of your farming. Here at Twin Oaks Community, the goal of our garden crew is to increase our self-sufficiency and reduce dependence on the cash economy. We aim to provide a diverse year-round supply of tasty, fresh organic vegetables and fruit for our intentional community and also to grow enough to process for out-of-season use. The increasing interest in buying local food and eating organic is creating a need for a dependable supply of local, sustainably grown winter vegetables as well as summer ones.

Before you wail with exhaustion at the thought of more work and no rest, let me emphasize that all farmers need time to rest, and this needs to be incorporated into the farm’s schedule. It might take the form of a complete shutdown of the farm’s interaction with the public or a slowdown that allows all the workers to take turns vacationing. Give careful consideration to what you can do to extend the season without overworking yourself, your crew, or your soil. If you decide to provide produce during the winter, you’ll find the pace is naturally slower: few weeds germinate, and established crops need less attention. It’s not a second hectic summer.

I’ve identified 16 factors that help us to keep good food on the table year-round.

1. Planning

During the winter we spend a few hours each week working on some aspect of planning the coming year’s work. This helps us make the best use of our land, money, people, climate, and crops. We also do some planning mid-year for August–December for the hoophouse and for the intensive raised bed area where we grow many different crops in quick rotation. If the situation changes, we can always change the plan. Having a map and a schedule helps us make the best use of the growing season and minimizes the need for last-minute, middle-of-the-field, brain-frying calculations in August. We create a field manual with all the most important maps, schedules, and crop specifications inside plastic sheet protectors. We keep the manual in our tool shed.

2. Research and information

One of the most important farm implements is the brain! Gathering (and retaining) information helps avoid silly mistakes in the field. Books, websites, seed catalogs, conferences, and field trips to other farms can feed the farmer’s mind and spirit and lead to better crops. A good filing system, in both paper and electronic formats, keeps the information accessible.

3. Caring for the soil

Compost, cover crops and organic mulches such as spoiled hay or old sawdust all improve the soil. Getting an annual or biennial soil test and amending with any needed lime, gypsum, or other minerals will help increase yields. A good multiyear rotation schedule for the main crops will also help get the most from your soil by varying what is drawn from it each year.

4. Maximizing plant health

Keeping plants growing well by preventing and controlling pests, diseases, and weeds leads to a longer productive crop life and a longer-running food supply. It’s vital!

5. Gearing up

Having appropriate, functioning machinery and tools, as well as an ample irrigation system, ensures that productivity is not limited by your equipment. Implements need to fit the scale of the farming and the number of people available to do the work. We’re growing on 3.5 acres (1.4 hectares). The equipment we have is workable, although not ideal. We use a John Deere tractor for disking, compost spreading, bushhogging, and potato furrowing, hilling, and harvesting; an 11 hp BCS walking tractor (with rototiller, rotary plow, and mower); many scuffle hoes; an Earth-Way manual push seeder; some drip irrigation; seven Rain Bird overhead rotary sprinklers; seven wheelbarrows; six Garden Way carts, and many stacks of plastic 5-gallon buckets. We also have lots of helpers.

6. Storage

We store potatoes in a root cellar; sweet potatoes, winter squash, pumpkins, garlic, and onions in a basement; carrots, beets, turnips, rutabagas, celeriac, and kohlrabi in a walk-in cooler; and peanuts in the pantry. Meeting the different storage requirements of various crops helps maximize their season of availability.

7. Transplants

Using transplants often makes multiple crops possible in a bed in one season because it reduces the length of time each crop needs to be in the bed. It also extends the season in the spring by allowing plants started inside in milder conditions to be set out as soon as the weather is mild enough, giving them a head start over direct sown crops. And it means overwintered cover crops can be left growing later (for example, until clovers, vetches, or peas flower), for improved soil nutrients.

8. Season extension

The supply of a crop can often be extended at both ends of its normal growing season. Usually, an extension of 2 or 6 weeks in the fall takes only a little extra vigilance and a modest investment in rowcover or shadecloth. Naturally, the further you try to extend the season of a crop beyond what is normal for your climate, the more energy it takes and the less financially worthwhile it becomes. We have recently discovered the wonders of biodegradable plastic mulch — it warms the spring soil and brings melons to maturity 3 or 4 weeks earlier.

9. Overwintering crops

Kale, collards, spinach, leeks, and parsnips can all survive outdoors without rowcover in our climate (USDA Winter Hardiness Zone 7a). We can harvest small amounts throughout the winter, and when spring arrives, the plants perk up and give us big harvests sooner than the new spring-sown crops. Arugula, mâche (corn salad), and some other small greens are very winter-hardy too.

10. Protected growing

A hoophouse (high tunnel) is a very good investment for winter crops as their rate of growth is much faster inside, and the quality of the crops, especially leafy greens, is superb. Even though we had expected good results from a hoophouse, we are still amazed, twenty years after building it, at just how incredibly productive it is. Also, working in winter inside a hoophouse is much more pleasant than dealing with frozen rowcover and hoops outdoors. Greenhouses and coldframes also offer opportunities for cold-weather crops.

11. Succession cropping

We plant outdoor crops here in central Virginia every month.

Admittedly the only ones we plant in December and January are multiplier onions (potato onions). We grow 9 plantings of carrots, 6 or 7 plantings of sweet corn, and 5 or 6 each of cucumbers, summer squash, zucchini, edamame, and bush beans. We do almost 50 plantings of lettuce! Southern peas and lima beans get 2 plantings. All this means that as one planting is passing its peak, a younger one starts to be productive. Some crops grow here in spring and again in the fall, so we make the most of both seasons. Examples include broccoli, cabbage, spinach, kale, collards, turnips, beets, potatoes, and many Asian greens. I recommend recording dates of sowing, first harvest, and last harvest for each planting. You can use this information to determine the best sequence of planting dates for keeping up a continuous supply.

12. Interplanting and undersowing

Sowing or transplanting one crop (or cover crop) while another is still growing is a way of increasing the productivity of the land. Sometimes it enables a cover crop to get established in a timely way that would not be possible if we waited for the food crop to be finished first. We interplant peas in the center of spinach beds in March and plant lettuce on either side of peanuts in April. We undersow our last sweet corn planting with oats and soybeans, which then become the winter cover. We undersow our fall brassicas with clovers in August to form a green fallow crop for the following year.

13. Food processing

We have a food processing crew who pickle, can, freeze, and dry whatever produce we don’t need to eat right away. They also make sauerkraut and jam. We make use of a solar food dryer and an electric dehydrator. Processed (or value-added) foods effectively lengthen the season of local food availability, without requiring out-of-season growing.

14. Crop review

During the main growing season, we don’t do a lot of paperwork. We record planting dates, noting the harvest start and finish dates for our succession crops. We label each crop in the field with a row tag. When the crop is finished, we pull up the labels and consign them to one of two plastic jars in the shed: “Successes” or “Dismal Failures.” On a rainy day in the fall, we transfer the information to the notes column on our planting schedule. At the beginning of the winter, we take time to discuss and write up what worked and what didn’t so that we learn from the experience and can do better next year. This is an example of those triangular cycles recommended in personal growth literature and management workshops, which rotate through three stages: “Plan–Execute–Review” or “Learn–Do–Reflect.”

15. Choice of crops and varieties

Every year, we try to introduce a new crop or two, on a small scale, to see if we can add it to our portfolio. Sometimes we can successfully grow a crop that is said not to thrive in our climate. Rhubarb works, but Brussels sprouts really don’t. We like to find the varieties of each crop that do best for our conditions. We read catalog descriptions carefully and try varieties that offer the flavor, productivity, and disease resistance we need. Later we check how the new varieties do compared with our old varieties. We use heirloom varieties if they do well and hybrids if they are what works best for us. We don’t use treated seeds or GMOs because of the wide damage we believe they do.

16. Lots of help

Last but by no means least, we arrange our work so that unskilled visitors and new community members can join in and be useful. It is sociable work, combining productivity with integration into the team.