Schooling has always been a hot topic, but the COVID-19 pandemic brought it into sharp focus. Suddenly, schools were thrust into uncharted territory, forced to adapt to challenges that highlighted just how interconnected and unpredictable our world has become. While some creative solutions emerged, many systems snapped back to outdated norms, leaving us wondering: how can we prepare students for the complexities of the future?

In this excerpt from the new book The End of Education as We Know It, author Ida Rose Florez explores how schooling and education must evolve to meet the demands of a rapidly changing, globally connected world.

Living and Learning in a Complex, Globally Connected World

Over the last several decades, the world and its problems have grown exponentially more complex than what Einstein and Russell decried in their treatise. Nuclear annihilation remains an existential threat. In addition, the climate crisis is nearing an irreversible tipping point, and grotesque economic inequities continue to widen.

These global problems emerged from our current ways of thinking.

Our current ways of thinking cannot fix them.

Even with the growing urgency, we still have not learned to think in a new way. We live with a collective false sense of security, trusting in our modern day marvels, believing our educated masses are immune to the perils of previous generations. Yet, despite knowing that in the very recent past huge populations of First Nations and Indigenous peoples were wiped out by viruses imported by European colonizers, even the most technologically advanced nations were caught unprepared by the COVID-19 pandemic.

COVID-19 awakened us to just how connected our world is and what that interconnectedness means for daily life. Prepandemic, we were hardly impressed when people flew nonstop from Sydney to New York. We shrugged off worries when Wall Street jitters rattled markets in Beijing. We took as normal that throw pillows sold on Amazon were designed in Italy and made in Vietnam with Australian wool. We ordered them on our phones, choosing two day delivery, not thinking about how the global connectedness that made that purchase possible might disrupt our lives.

That naivety is gone. We now know a microbe can jump species half a world away, show up in our local grocery, kill millions in mere months, shut down schools, overwhelm state of-the-science medical systems, and thrust unemployment into the depression era stratosphere.

COVID-19 set most heads spinning, but not everyone was surprised. While global connectivity inched its way into every societal cranny, some professions paid attention. It was their job to pay attention. For decades, epidemiologists, cybersecurity experts, military strategists, and data scientists, among others, have studied how complexity behaves when increasing numbers of people interact in an increasing number of ways. Certainly, economists and biologists have reason to study complexity, but it hasn’t been at all clear what complexity science has to do with schools.

Until COVID-19.

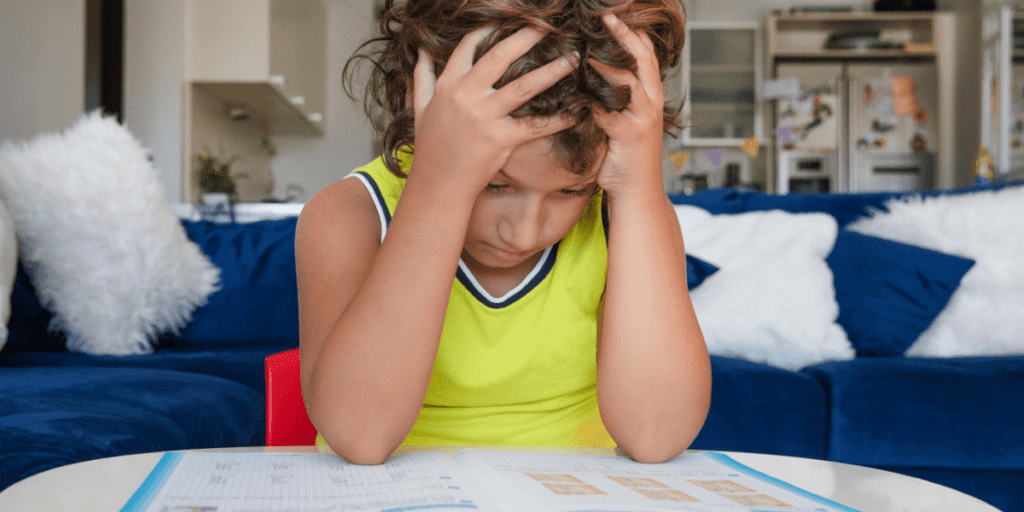

In March 2020, the global dynamics that delivered pillows to our porches landed squarely in the laps of superintendents, teachers, parents, and workers in every organization that interfaces with or depends on education as we know it. With few exceptions, the impact of COVID-19 caught school systems, from early learning through higher education, completely off guard, leaving teachers scrambling to craft Zoom friendly lessons while delivering classes with unfamiliar software. Parents turned-crisis-homeschoolers donned brave faces for what was supposed to be a two week stint.

As weeks turned into months and as proms and commencements were canceled, parents posted Facebook memes of throwing back whiskey by nine a.m. while promising to never again vote down a teacher raise.

The New Normal

To ease our angst, we like to think the COVID-19 pandemic, and the accompanying educational havoc, was an anomaly. As we bared our arms and got our vaccinations (and hoped others would too), we soothed ourselves with talk of getting “back to normal” when “this is over.”

But the complexity we are in will never be over.

The COVID-19 pandemic was not an anomaly.

Global complexity, and its attendant impacts, has been the new normal for quite some time. As the Omicron variant eased up in the United States, China was shutting down major cities which worsened global supply chain difficulties, and Russia attacked Ukraine, keeping the global economy and relations between countries uncertain and unstable. As the pandemic eased and supply chains recovered, all hell broke loose in the Middle East.

In this new normal, we learned something: education can happen in ways no one previously thought it could. Kids can learn from home as well as in a classroom, schedules can be flexible, pickup basketball in a corner lot or yoga with the dog in the living room can count as phys ed. But as health restrictions eased and schools reopened, rather than incorporating this new flexibility, schools ditched most adaptations and snapped back to rigid conformity. One parent of a high school sophomore told me, “My son has had all kinds of freedom you normally don’t have at his age. He can go out in the neighborhood, go into town, in the middle of the day. Next year they’re all going back in.”

Back in.

Back into what? To a system far removed from the complex reality of everyday human life and from the new ways of thinking Einstein and Russel begged us to learn more than sixty five years ago.

Education as we know it was not designed for this new normal.

It was never intended to prepare children for living in this level of global complexity.

We try hard to respond to these challenges and threats through our governments, organizations, and as individuals, but our actions fail us. No matter what we do, stability and lasting solutions elude us. It’s time to realize that we will never cope with this new world using our old maps. It is our fundamental way of interpreting the world — our worldview — that must change.

––Dr. Margaret Wheatley, Leadership and the New Science

We must learn to think in a new way.