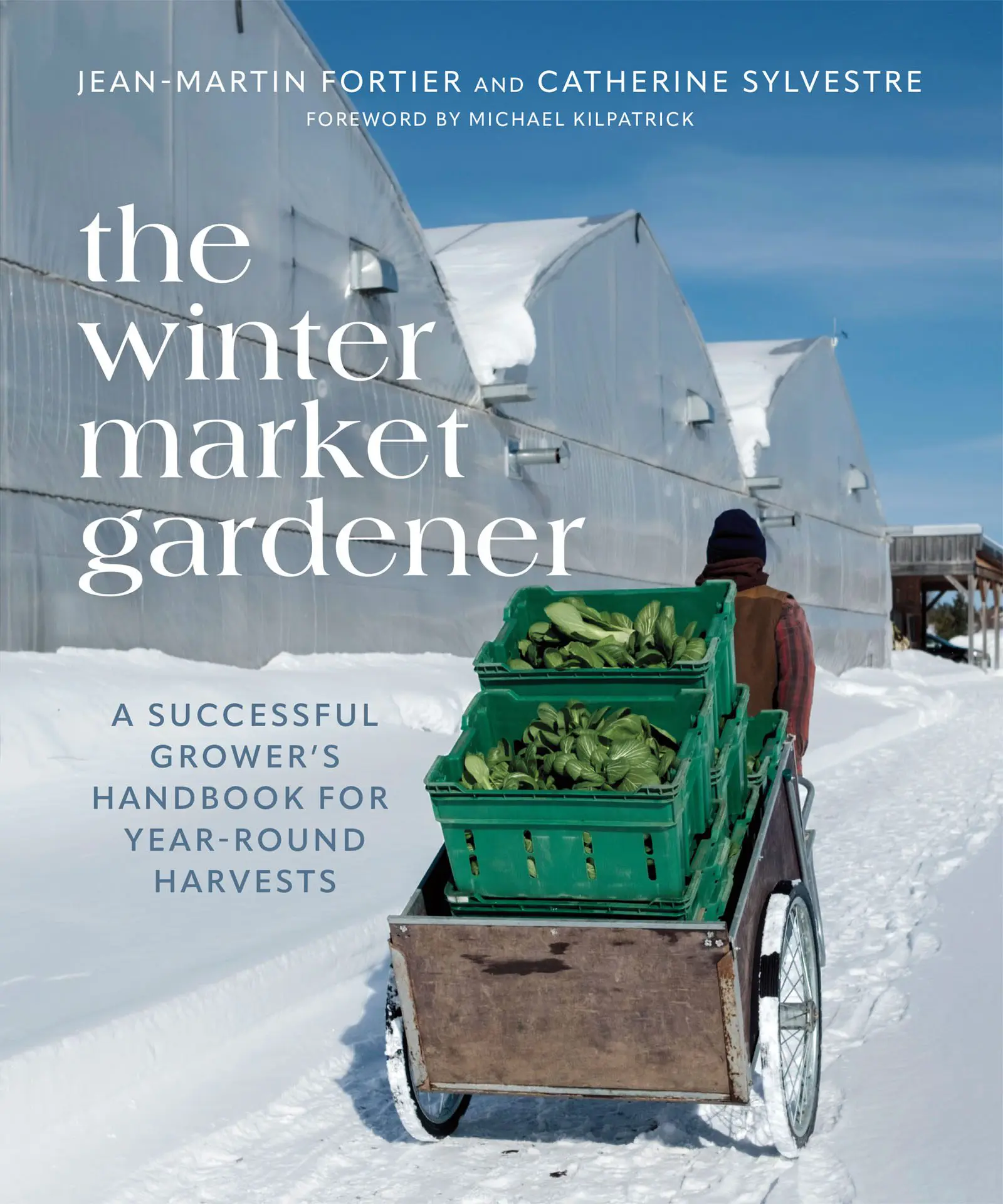

With summer in retreat, and fall upon us, you might think it’s time to put your gardening tools away. But don’t hang up your gloves just yet—there’s still a lot of growing left to do! Welcome to the world of winter gardening. As winter’s frosty blanket covers the landscape, growing and harvesting vegetables presents both a unique challenge and a rewarding adventure. The key is to protect your crops from those biting cold winds that can dry them out and push them to the edge. While many vegetables can handle cold temperatures, they struggle when faced with harsh windchill and sudden temperature swings. The trick to a thriving winter garden is creating cozy microclimates that shield your plants from the elements. In this excerpt from The Winter Market Gardener, Jean-Martin Fortier shares practical strategies and innovative ideas to help your winter garden thrive despite the chill.

Necessity is the mother of invention.

— Plato

Growing and harvesting vegetables in the heart of winter is an adventure that starts with protecting crops from bad weather, especially from cold winds. It’s crucial to understand how the wind, through its drying effect, can damage them to the point of threatening their survival. Like us, vegetables can be comfortable in the cold, but we run into trouble when conditions are exacerbated by windchill. Drastic temperature fluctuations can also make crop survival precarious. The key to success is creating microclimates that protect crops from harsh winter weather.

As explained previously, 19th—and early 20th-century vegetable growers used cold frames to protect their crops from winter airflow. Before that, vegetable growers in Paris used glass bells (cloches). These protected each tomato plant, lettuce head, or any other vegetable they tried to force into producing earlier in the season while conditions were unfavorable for growing.

The cold frame method can still be useful today, and it is not uncommon to meet older gardeners who rely on it. Glass bells, however, are now a thing of the past. In our day and age, who would bother to remove and put back each bell in their garden?

With advances in technology, tunnels have now replaced cold frames, and the bells were replaced by what are known as row covers. Today, the combined use of these two simple technologies is at the heart of winter growing for people who farm in sync with the seasons.

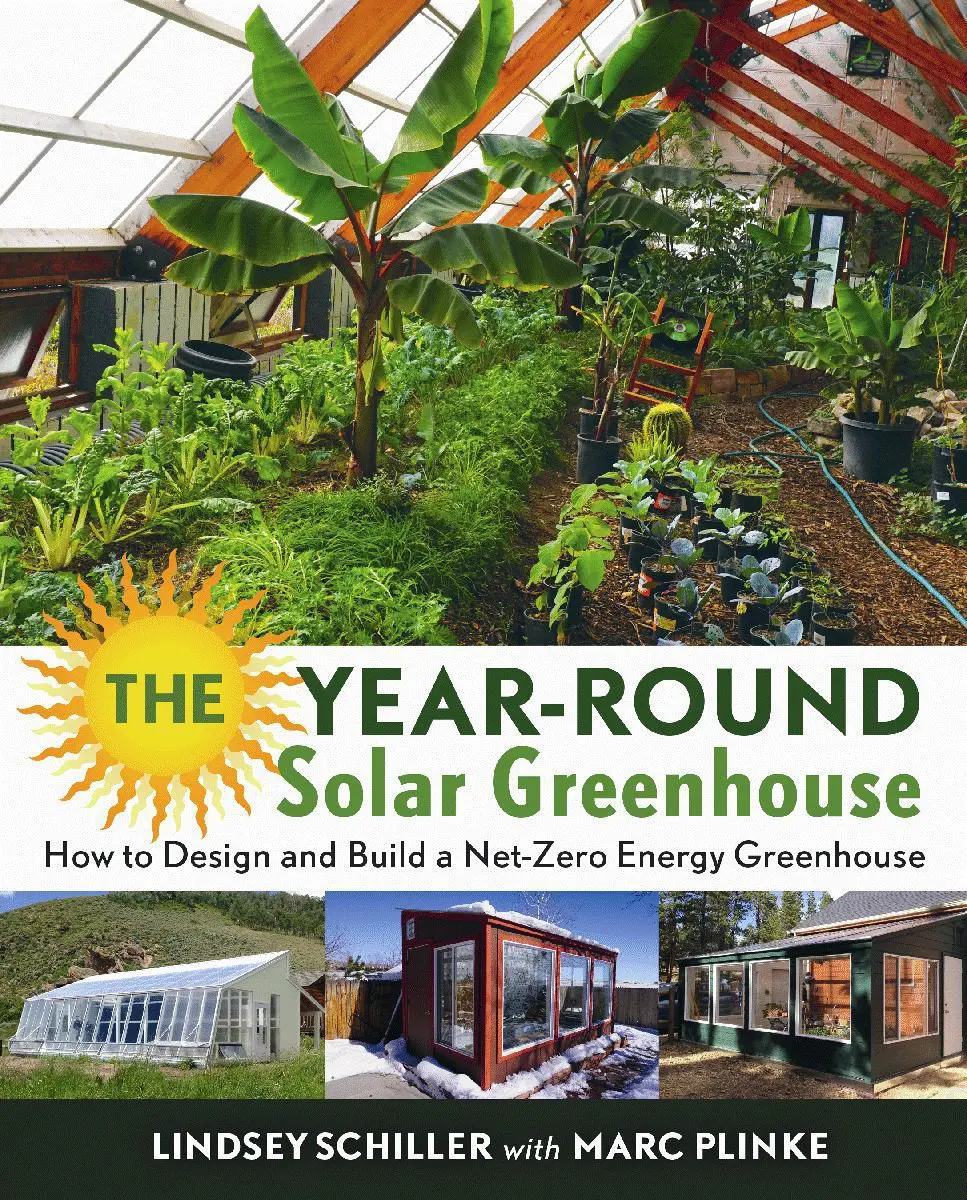

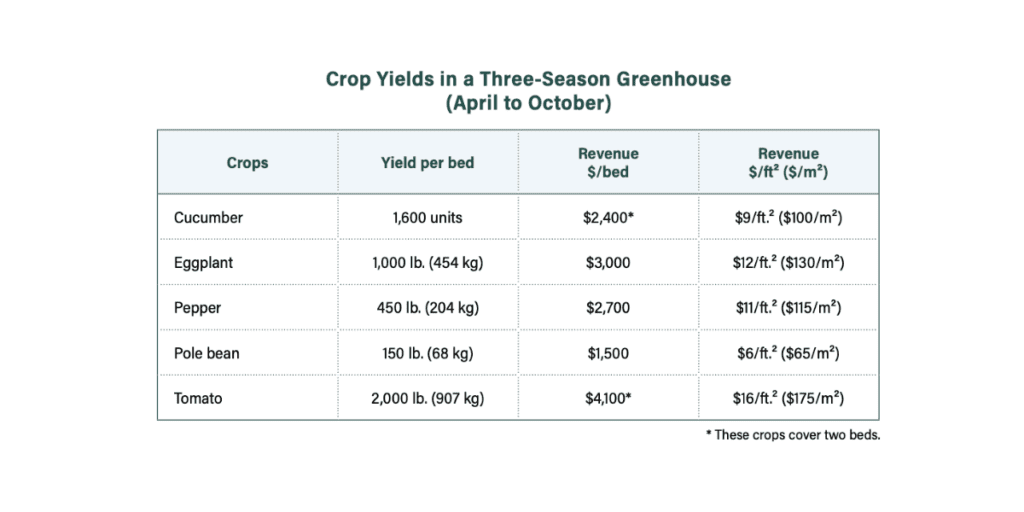

The truth is, it’s easy to grow vegetables in the winter in a heated greenhouse. With the help of ever-evolving technology, we can get around seasonal realities. A well-insulated modern greenhouse, equipped with a heating system and grow lights, can recreate the perfect climate, no matter how harsh the weather is. The only constraint then becomes the cost associated with the initial install and climate regulation. But the cold nights of our northern winters make it extremely expensive to recreate optimal growing conditions.

This explains why, in Quebec, vegetables grown year-round are mainly tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers, and some climbers like beans. These products yield over quite a long period (six months or more) and generate the highest revenue per square meter of crop surface. The greenhouse industry has developed highly precise crop management sequences to optimize growing conditions for these vegetables and ensure that production is profitable.

That being said, it is also extremely energy-intensive to grow these heat-loving vegetables in winter. It requires modern facilities that are highly expensive to deploy. As a result, industrial greenhouse complexes tend to be the only operations capable of taking on this kind of project.

In recent years, several investments have been made to increase the production of these crops grown for the Quebec market and even for export.

In fact, in 2021, to promote Quebec’s food autonomy, the provincial government granted a $30-million loan to a large greenhouse company to build the biggest greenhouse complex in Quebec, with a 37-acre (15-hectare) footprint. Without disparaging the initiative, take a moment to imagine how the landscape would look if these funds had financed the development of 200 small vegetable farms. They could easily add three to four months to their production season by acquiring small greenhouses. And for the rural communities that these small farms serve, the economic impact would be overwhelmingly positive.

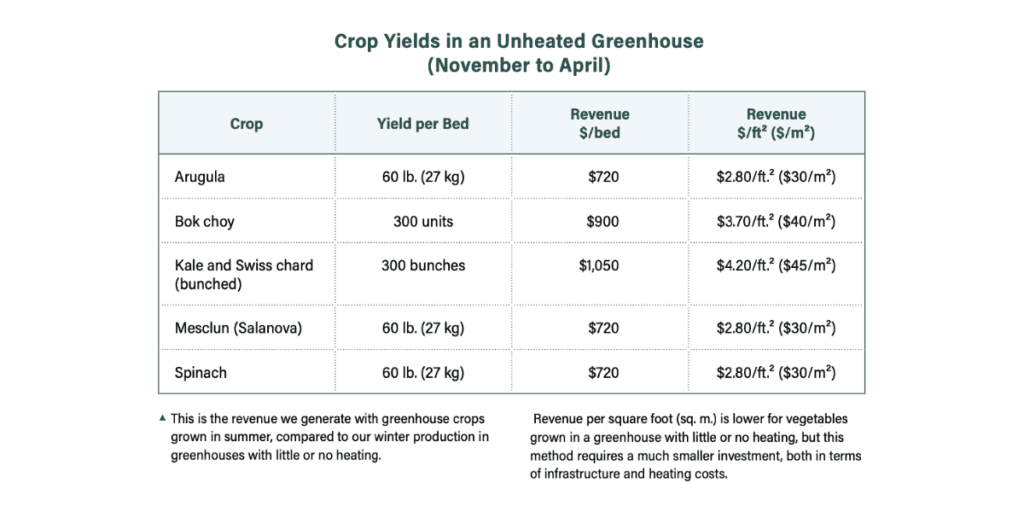

We firmly believe that in a northern climate, a local, diversified, and quality vegetable offering doesn’t have to come from mass production in heated greenhouses. This means choosing cold- hardy crops that don’t require artificial light. With this strategy, small farms can capitalize on the protection provided by a greenhouse or a simple shelter in winter to grow vegetables year-round, with minimal or no heating. Vegetables that are well-suited to colder temperatures include spinach, kale, mesclun, bok choy, arugula, and Swiss chard.

Simple Shelters

At Ferme des Quatre-Temps, we have perfected the art of using the right simple shelter at the right time. We install various equipment, such as caterpillar tunnels, low tunnels, permanent high tunnels, and row covers, depending on the needs of the crops and the time of the season. Each shelter is suited to a specific use, and we sometimes combine them. The easiest way to understand their purpose is to explain the role of each one.

Most vegetables grown in modern greenhouses in the winter, like tomato, cucumber, and eggplant, require artificial lighting, which is expensive and generates significant light pollution. For the towns and ecosystems surrounding the complexes, there are negative repercussions; they emit light emissions for up to twenty hours a day, and disrupt circadian rhythms in both animals and humans. While the horticultural industry is increasingly relying on LED lights, the long-term health effects of consuming vegetables produced with artificial lighting are not yet known.

ROW COVERS

Row covers are large pieces of nonwoven polymer fabric that help when ambient temperatures are nearing 28°F and 27°F (–2°C and –3°C). Made of permeable material, they allow air, light, and water to pass through. When protecting crops, row covers retain heat near the ground, which increases temperatures while helping to conserve moisture. In doing so, they provide a few additional degrees of frost protection. By acting as physical barriers, row covers also help protect seedlings from weather events, like driving rain and strong winds, and from pests.

Row covers are available in different thicknesses (calculated in ounces per square yard or grams per square meter). Your choice of product will depend on the situation and season. On our farm, both in spring and fall, we use row covers with a 0.55 oz./sq. yd. gauge (19 g/sq. m). They are durable (when handled with care, they will last more than one season) and provide 85 percent light transmittance compared to an uncovered crop. This cover, called P19, also provides an increase in temperature of approximately 3°F to 4°F (1.5°C to 2°C).

For optimal results, row covers are spread out over hoops made of galvanized steel wire that prevents them from touching the crop’s leaves, which could cause frost damage. In winter, we use row covers inside other shelters for additional protection against the cold. Sometimes, we even use two or three layers of row cover.

Good row cover management is essential in unheated greenhouses and tunnels as it helps limit overnight heat loss. We recommend using the following guidelines to ensure success:

- When the temperature in the greenhouse is near freezing (32°F, 0°C): Set up one P19 row cover on the crops.

- When the temperature in the greenhouse is 23°F (–5°C): Set up two P19 row covers on crops, layered one over the other.

- When the temperature in the greenhouse is 14°F (–10°C): Set up three layers of P19 row cover on crops.

- When day length is less than 10 hours: Leave the row covers on the crops at all times. Heat built up under row covers will contribute to a significant increase in overnight temperatures around the plants. During the day, the sides of row covers can be raised slightly to promote ventilation.

- When day length is longer than 10 hours: Remove the row covers between 9 a.m. and 3 p.m. on sunny days, unless temperatures in the greenhouse are at or below freezing. At this time of year, daylight hours are long enough to justify removing row covers.

LOW TUNNELS

In the fall, low tunnels are the perfect low-cost solution for extending the season until the first big snowfall. They cover a smaller surface area than caterpillar tunnels (two beds instead of four), but are stronger, easy to install, and highly affordable. These simple structures can be moved throughout the farm and can withstand some snow loading.

Low tunnels are made from galvanized steel tubing (EMT), which is sold in hardware stores and shaped using a pipe bending machine. Compared to hoops that hold up row covers, low tunnel structures are much stronger, and they can, therefore, support a polyethylene film (transparent greenhouse plastic).

To install the tunnel, we start by placing rebar into the ground. Then, we fit the hoops over the rebar and cover the frame with a layer of transparent plastic. The tunnel is secured by ropes that are tied to the bases of various arches and that run over the plastic. At each end of the tunnel, the plastic extending past the hoops is roped to a piece of rebar.

CATERPILLAR TUNNELS

Unlike low tunnels, caterpillar tunnels cannot support any snow load. Every year, we have to remove their plastic covering before the first big snowfall. This disadvantage doesn’t deter us from using them, however, as they are one of the simplest, most affordable, and effective solutions to extend the growing season.

When compared to high tunnels, the biggest advantage of caterpillar tunnels, aside from their price tag, is their mobile design. Because these structures can easily be assembled and dis-assembled, they can be moved anywhere in the garden at any time of the season. In early spring, we position them over our first seedings in the field, to protect them from those final cold nights. Then we move them onto tomatoes, peppers, and melons, which always need extra heat in the summer. When the first frost arrives, we move them once again to protect fall crops that have begun growing in the field. Vegetables like spinach, mustard, and baby kale can withstand several frost events and continue to grow thanks to the microclimate created by a caterpillar tunnel.

Caterpillar tunnels are one of the simplest and most effective solutions for extending the growing season.

To build a caterpillar tunnel, you can choose between many techniques and materials. The simplest approach requires only galvanized steel tubing (bent using a pipe bending tool), rebar, straps, rope, and polyethylene film. The arches are installed 5 feet (1.5 m) apart and are anchored onto the rebar, which is sunk halfway into the ground. To reinforce the structure, a strap connects every arch at its apex. At each end of the tunnel, that strap is tied to two 6.5-foot (2 m) T-posts that are securely planted into the ground at a 45-degree angle. The plastic then goes between these two bars, which are tied together to maintain tension. Lastly, like with the low tunnel, ropes go over the transparent plastic and are tied to the bases of the arches. Using a tensioning knot in each rope, the plastic can then be pulled taut. The tunnel looks like a long caterpillar, which is how the structure got its name.

For ventilation, we open the tunnel by manually lifting the plastic along the sides, and the ropes keep the plastic from moving.

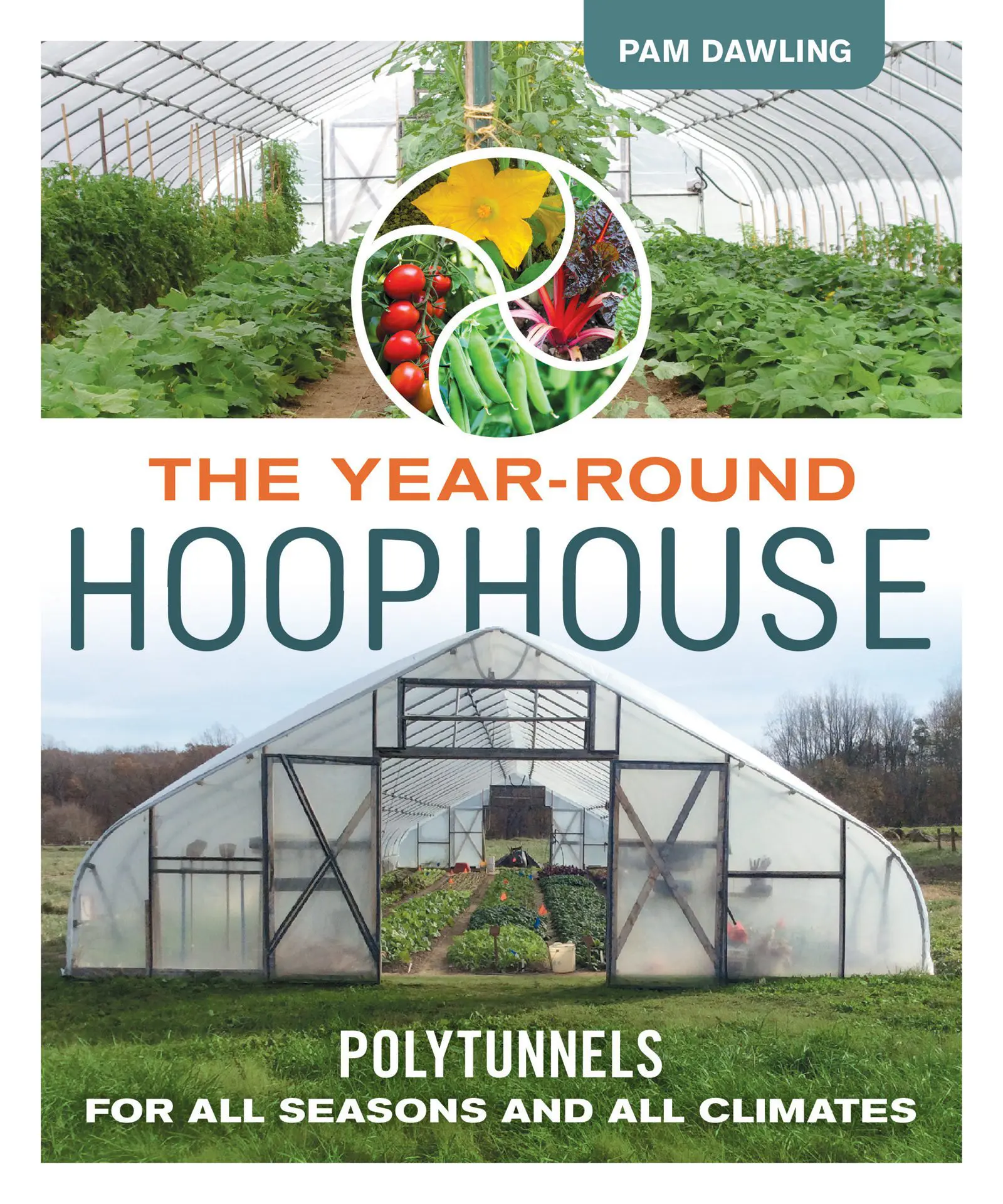

HIGH TUNNELS

A high tunnel (also known as a passive solar greenhouse, hoop house, or polytunnel) is a permanent structure made from semicircular steel arches, which are bolted and covered with a polyethylene film. Unlike greenhouses, high tunnels are not tall and have a simple, often more rounded structure. Generally, they are 20 to 26 feet (6 to 8 m) wide, and the apex is no more than 10 feet (3 m) high, while length is variable, ranging from 50 to 150 feet (15 to 45 m). At Ferme des Quatre-Temps, we’ve standardized all our permanent tunnels to a 100-foot (30 m) length.

These tunnels are sometimes referred to as cold tunnels because, unlike greenhouses, they are unheated and are therefore less insulated. Of course, this means they are also more affordable. The tunnels have roll-up side openings, and large doors at the front and back, which are more than enough to provide good ventilation in the tunnel.

Unlike low tunnels and caterpillar tunnels, high tunnels cannot be moved because of their more robust anchoring system. When properly installed, they can withstand the weight of a heavy snowfall without collapsing. This makes them excellent four-season tunnels. Their versatility throughout the growing season is an undeniable asset, as they protect early crops in spring and late crops at the end of the season and also provide the perfect summer conditions for heat-loving crops. Plus, when fall comes along, you can plant winter vegetables in the high tunnel, to provide continuous production until the following spring.

Permanent tunnels come in many shapes and sizes, and most greenhouse manufacturers sell some kind of high tunnel. The price for a new model depends on the type of reinforcements, as well as the width and length; in any case, this tunnel is one of the best investments a farm can make. Revenue generated by crops grown this way will surpass construction costs within a few seasons, if not the first one.

Because these tunnels are permanent structures, you need to carefully consider their loca- tion, especially with regard to soil drainage. In the spring, poor drainage will cause beds to stay wet for too long and delay early crop plantings. The best solution is to install agricultural drains along the perimeter of the structure. Leveling the ground is also effective but requires heavy soil work. Furthermore, do not install tunnels near other buildings or large trees, as they could block sunlight part of the day. When deciding where to place a tunnel, consider an orientation that maximizes sun exposure and that is parallel to prevailing winds, to minimize snow accumulation on the shelter.

Permanent tunnels are simple and affordable shelters that provide profitability in winter and do not require excessive heating or complex technological facilities.

High Tunnel vs Greenhouse

In both cases, we are referring to permanent structures that protect crops from cold winds and create a favorable climate for growing. If you’re new to this, it’s easy to get confused. Unlike high tunnels, greenhouses are heated, and are therefore better insulated. They can be made of glass or two layers of plastic, which are constantly kept apart by a blower that pumps air between them. Greenhouses also have several systems that allow for precise climate control, and they can be set up with equipment that automates tasks.

The length, width, and height of a greenhouse will vary between models. For most small organic farms, this structure will be no larger than 35 feet × 100 feet (10 m × 30 m).

| Now that you’re aware of how you can extend the growing season with proper crop protection, you might be curious about which vegetables are best suited for a winter harvest. To help you out, we’ve got a handy Winter Planting chart from the book that outlines the ideal dates for your sheltered crops. Feel free to download it and start planning your winter garden! Download the Winter Planning Chart |