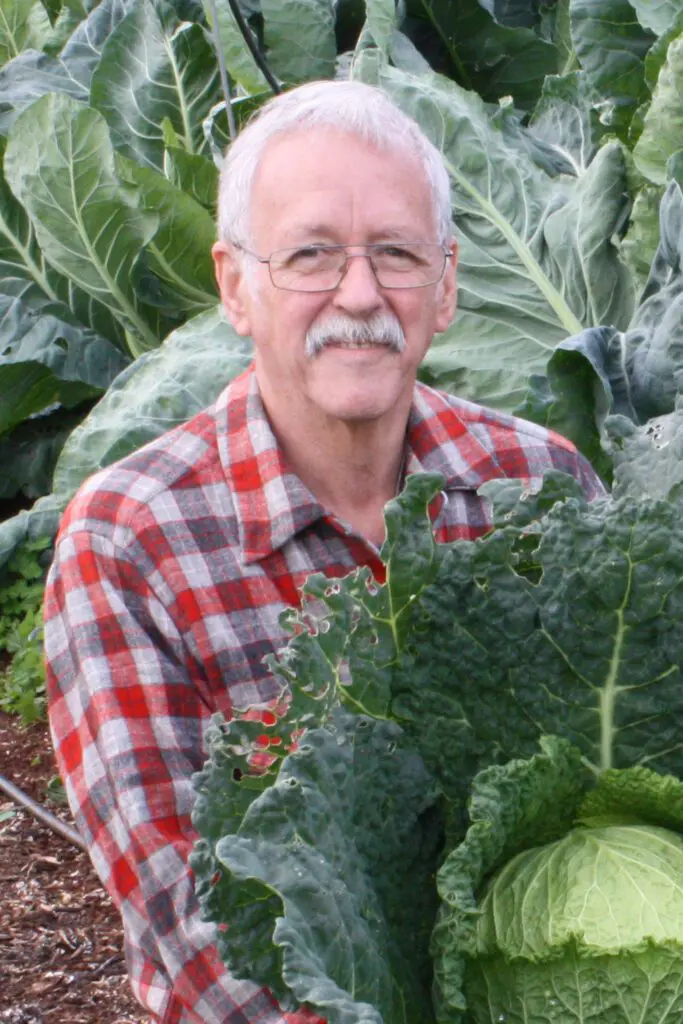

Have you ever wondered why no matter how hard you try, your garden looks nothing like the gardens in the gardening columns? You aren’t alone! In The Intelligent Gardener, Steve Solomon explains why it can be hard – if not impossible – to achieve the same results as those in the gardening columns. If you’d like to become an intelligent gardener, there’s never been a better time.

Garden Writers

There are oft-repeated errors in veggie gardening books, and an even denser concentration are found in gardening magazine articles. After all, we garden writers are only ordinary humans — with all the usual flaws and warts — who passionately share your interest in food growing.

Garden writers are well meaning; they try to help others succeed by sharing their own successes. I do not usually sense obsessive egotism distorting garden writing, nor do I strongly smell “I’m better than you are,” seeping out the cracks in gardening magazines. I suppose that’s because there’s little about any home gardening opinion that can threaten anyone else’s prosperity or survival. Most garden writers positively push what they believe succeeds, while ignoring those who disagree. That’s been my approach too, until writing this book. In this book, I try to broaden the reader’s opinion about what organic is and what it should be — and that can be a touchy minefield. Since I’m setting out to change opinions, it seems sensible to help lighten your load of previously acquired views by pointing out their source.

Few garden writers received a formal horticultural education. That’s positive in a way, because those who graduate from a university, especially with an advanced degree, usually have been so traumatized from having to produce professor-pleasing papers that rarely are they ever again able to write freely. I think it’s near-impossible for someone with an MSHort to write for the home-garden market. On the other hand, garden writers are glib, but they lack proper scientific foundations. They learn from their own experience and/or from the garden books and magazine articles written by other garden writers who have similar limitations. Having avoided the pitfalls of academic horticulture, they lack the formal science needed to appreciate the common flaws found in gardening information. Thus, errors get uncritically transmitted from one generation of garden writer to the next. And with each retelling, the error acquires more authority, seems more correct, because it has been said by Everybody Else so many times for so many years. Garden writers usually lack broad experience. They typically start out being over the top about growing backyard vegetables and consider they have achieved enormous success. But these great successes can be pretty subjective and actual results quite ordinary because they are comparing their results with their neighbors’. I did that. In my first few books, I enthusiastically, and with great sincerity, encouraged my readers to “do as I have done, and you’ll have as great a success in your backyard as I have had in my own.” But then I saw Dr. Jim Baggett’s OSU variety trials expertly grown on Class I soil. I realized I had a long way to go before I could match those results.

A garden writer usually gardens on one type of soil, in one climatic zone, and perhaps in a uniquely favorable (or particularly challenging) microclimate within that general climate. Contributing factors, such as the salt levels in irrigation water, or a particularly favorable backyard microclimate often go unrecognized, or the gardener just ignores them in the flush of triumph. I did that. When I began growing variety trials, I’d only been gardening for six years, four of them in southern California on pretty good soils. Oregon was entirely different. At that time, I reckoned that growing trial gardens on lousy soil in a short-season, chilly coast range valley was a plus for my business.

Although it took a lot of inputs to make that silty-clay subsoil grow things acceptably well, I was able to eliminate the weakly rooting or chill-intolerant varieties that didn’t thrive. Since most gardeners don’t have high-quality agricultural ground or live in banana belts, varieties capable of performing in my trials gardens would do well anywhere in Cascadia if given half a chance. But my how-to-garden opinions were distorted in those days by the enormous amounts of inputs it took me to grow decent crops. Consequently, my books from those years advised the overuse of seed meal and the use of far more organic matter than I now consider necessary, even on silty-clay subsoils. In fact, if you really want to embarrass me, get one of my early garden books and quote back to me some of my viewpoints from that era.

Organic Gardening magazine educated my cadre as we came of age. And my group has been educating everyone younger. The dogma underpinning what North American garden writers have long been promoting is best appreciated by reading J.I. Rodale himself. His books, Pay Dirt, The Organic Front and The Healthy Hunzas, are slim and easy to read, and I’ve put them on the Internet for free download. If you fancy yourself an organic grower, I urge you to have a read and see where some of your opinions originated from.