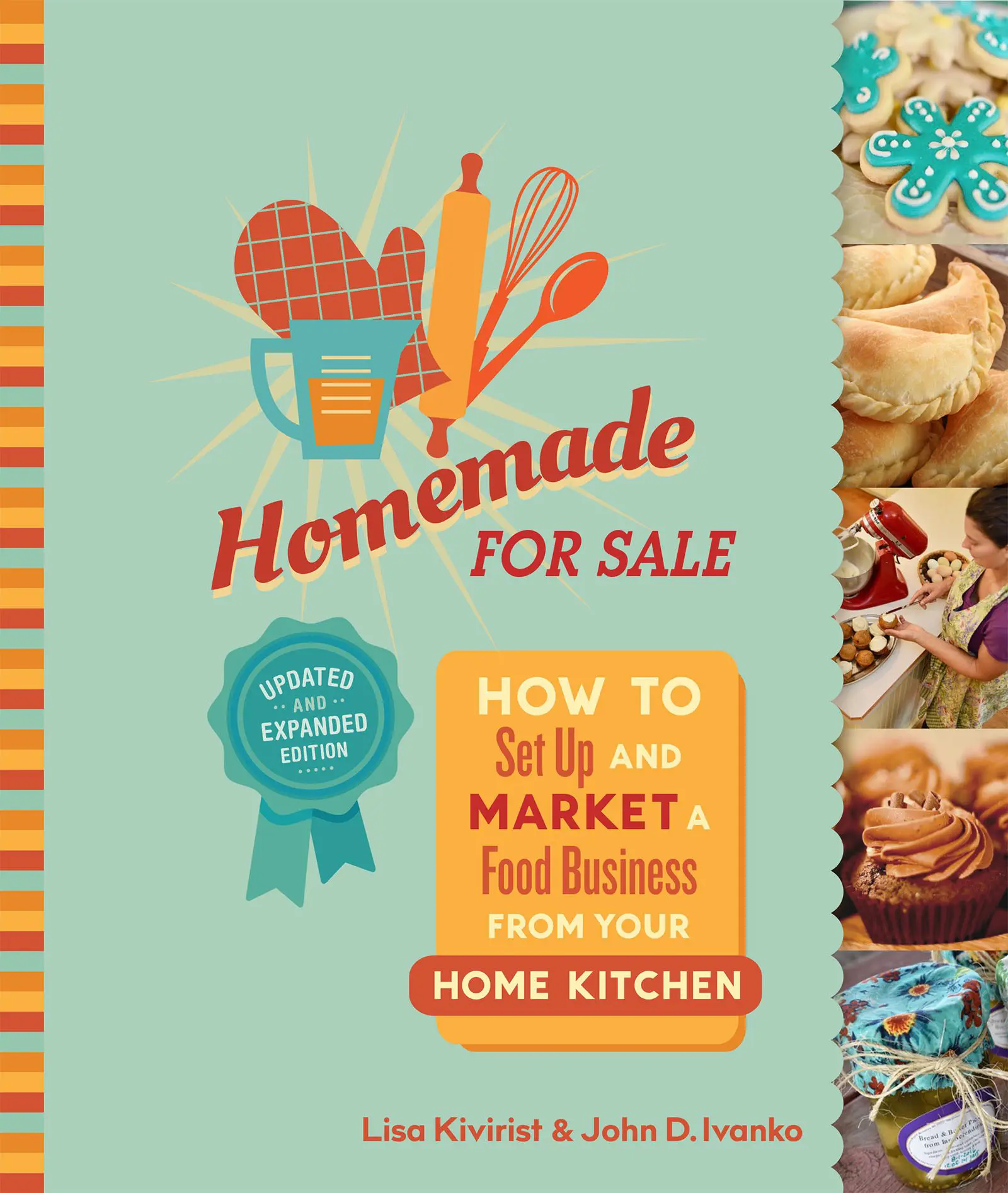

Homemade for Sale, Second Edition is the authoritative guide to launching a successful food enterprise from your kitchen. It covers everything you need to get cooking for your customers, providing a clear road map to go from ideas and recipes to owning a food business.

In this excerpt, author Lisa Kivirist guides us through the process of determining which products can be safely and legally produced for sale in the home kitchen.

What’s Cooking?

You may love to bake, can, or cook up a storm in the kitchen. That’s a great foundation for a cottage food enterprise. But there are a few steps to go through transitioning from being a “home cook” or “hobbyist” to being a “food entrepreneur.” This chapter examines some of your options and opportunities as a CFO, defined by the cottage food law where you live.

Cottage food laws vary a lot by state. The reason for this current patchwork of laws dates back to one of the underlying principles our country was founded upon: states’ rights. In the US, the Founding Fathers believed in giving independence and governing authority to the states on many issues.

The way that works today regarding food is the FDA publishes the Model Food Code, a model for the states to base their food regulation on— all 700-plus pages of it not including supplements. The Model Food Code provides a scientifically sound technical and legal basis for the food industry as a whole, and historically, states have generally abided by it as it relates to food establishments. But times are changing. As mentioned previously, both the Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic, among other considerations, have led states to abandon FDA food safety laws when it comes to foods produced in home kitchens. State exemptions made for foods sold at charitable bake sales have been extended to foods made in home kitchens. Because cottage food laws don’t cross state lines, only concern yourself with what’s required in your state. That’s simple enough, right?

There are four key questions you need answered in your state’s cottage food law before you get started:

- What products can you sell?

- Where can you sell your products?

- How are you allowed to sell your products?

- How much can you sell of your products?

Once you’ve answered these questions and understand how the cottage food law operates in your state, you’ll then need to figure out whether what you love to make is worth selling. If people are clamoring for your pretzels, that’s an excellent sign. In the end, your ability to sell products is based on creating items your customers want, need, and are willing to buy at a price that they, not you, determine. That’s where marketing—covered in several chapters of this book—comes in.

1: What Products Can You Sell?

There’s a reason for you to first see what types of products you can produce under your state’s cottage food law. It’s the classic glass-half-full versus glasshalf-empty scenario: focus on what you can legally make and don’t waste time, energy, and money spinning your wheels on what you can’t. Don’t complain, just cook.

Your state’s legislation will specifically outline those “non-hazardous,” also called “potentially non-hazardous,” food items you can produce under cottage food law. Some states also call these shelf-stable products “Time-or-temperature-controlled for safety (TCS)” foods. In the simplest terms, the conventions used to define such food are low-moisture and high-acid. Sometimes the legislation will itemize what you can or can’t sell.

“Non-hazardous” is the keyword, which we’ll use throughout this book. You don’t see that term used in recipes, right? By scientific definition, it refers to an item, usually a baked good, that has a low moisture level, measured as a water activity value of 0.85 or less. Or it can be a high-acid food, measured by an equilibrium pH value of 4.6 or lower. Some state legislation includes this exact verbiage about moisture levels and pH values.

Your state may also define other non-hazardous food items you’re welcome to sell. The two types of foods most widely approved under cottage food laws are low-moisture baked goods and high-acid canned foods like pickles or preserves, each explored next.

Baked Goods

Every state has cottage opportunities for selling baked goods. Baked goods are so prevalent in cottage food legislation because it’s hard to mess up a loaf of bread or a chocolate chip cookie from a food safety perspective. Politicians, if nothing else, are mostly risk-averse and conservative. Freshly baked non-hazardous baked goods are in a different food “safety zone” than something like canned green beans, a low-acid canned item you’ll never see on an approved list.

A simple way to understand non-hazardous baked goods is by asking this question: Does your item require refrigeration? If, like a custard pie, it does, then you cannot sell it in nearly all states with cottage food laws. However, here are some common examples of items you can bake and sell to the public:

- Bread loaves

- Cakes

- Cookies

- Muffins and scones

- Biscuits

- Crackers

Understand what your state defines as a baked good as sometimes this also includes products that don’t technically go in the oven but are perfectly non-hazardous such as rolled oats, nuts, and peanut butter to make an energy bar or trail mix. Depending on your state, these types of products may be covered separately in other categories (read on!), but they wouldn’t be defined as baked goods.

Check with your state’s law for the definitive rule on what is allowed. You might live in the state with an oddball exemption, for whatever the reasons, to what can be baked in the rest of the states. Pennsylvania, for example, is the only state that allows dried meat jerkies so far. Iowa allows licensed home-based food operators to sell cheesecakes, cream pies, and even items made with either meat or poultry from a state-approved source.

Missing from the approved non-hazardous baked goods list are any items filled with something that needs refrigeration. Moist fillings increase the moisture level and thereby increase the potential for harmful bacteria to thrive. There are a lot of variations on what a “filled” baked good can mean. Again, some states give specific guidelines while others may require you to contact the agency for clarification.

High-Acid Canned Goods (Pickles, Preserves, and Salsa)

Second to baked goods, many cottage food laws permit high-acid canned items made in home kitchens. The “high-acid” refers to fruits and vegetables that are either naturally high in acid, such as tomatoes, or that become acidified through pickling or fermenting. To be considered high-acid, these products must have an equilibrium pH of 4.6 or less. If your memory of tenth-grade science is a bit hazy, this pH number measures acidity; the lower the number, the more acidic the food item.

Examples of high-acid canned products include:

- Jams and jellies

- Pickled vegetables and fruits

- Salsa

- Sauerkraut (canned only)

- Chutneys

- Applesauce

Cottage food laws only refer to canned items processed in university extension-approved methods such as a hot water bath. High-acid items that don’t qualify in the legislation are refrigerator pickles or pickles made in a crock. Again, for the purposes of nearly all cottage food laws, if your product requires refrigeration, you can’t sell it. Check with your state’s law, because there increasingly seems to be a state or two that offers an exemption, for whatever their reasons, to some of the hard-and-fast rules. Illinois, for example, does allow certain fermented foods.

Unlike water activity level, pH can be measured at home if permitted by your state. You can use a pH meter, which needs to be properly calibrated on the day it is used. More common are paper pH test strips, also known as litmus paper; you simply dip these in a sample jar and the color will turn based on the acidity level and related pH number. Paper strips work best if a product has a pH of 4.0 or less; the strip’s range should go up to a pH of 4.6. Depending on your state’s rules, you may need to do a pH test on each batch or over a state-defined time frame. While expensive, a pH meter can provide a more exacting measurement of acidity.

Canning and creating high-acid products are very different processes than baking. Canning items, whether high-acid or not, is more science than culinary art. While you can alter, experiment with, and personalize your biscotti recipe until it is uniquely your own, this isn’t the case with canning recipes. At best, you’ll be able to adjust your spices and ratios of vegetables.

There are plenty of university extension-sanctioned recipes that have been thoroughly tested, from classic items like strawberry jam to more modern delicacies such as garden chutney and sweet pepper relish. Some states allow specific canning recipes from sources like the current edition of The Ball Blue Book of Preserving. But note that just because a recipe is in a canning cookbook doesn’t mean it will qualify under the state law. Just follow the state-mandated recipes and protocol and you’re good to go.

What if you want to use your great-grandma’s special family recipe for blackberry preserves? Some states will allow you to alter and create your own recipes after you complete the Master’s in Food Preservation course. This is similar in format to the Master Gardeners program, also through university extension. There seems to be a revival with this new home-canning movement. The Master’s in Food Preservation is a one-day intensive class that goes into the nitty-gritty science of pH and food safety procedures. Once you complete it, you can serve as a community education resource for local folks with canning questions. Or a Master Canner in your community may be able to review and approve your recipe.