Plant Science for Gardeners by Robert Pavlis is an entertaining and accessible guide that empowers growers to analyze common problems, find solutions, and make better decisions in the garden for optimal plant health and productivity. So, whether you’re a home gardener, micro-farmer, market gardener, or homesteader, this is the perfect guide for you. Today, we wanted to share an excerpt from the book that explains more about roots and their basic structure.

Roots

Roots are not very well understood by gardeners mostly because they hardly ever see them. They form a vital part of a plant and root health should be a priority for gardeners; it starts with buying the plant.

Plants are purchased based on what is showing above the pot, but it is a good idea for buyers to turn over the pot and knock out the plant so that you can have a close look at the roots. You might feel awkward doing this in a nursery but no one has ever said anything to me and I do it all the time.

In most cases the roots should be white and firm. You should see some new root tips growing around the outside of the pot, but the outer surface should not be covered with circulating roots because that indicates a plant that was not repotted correctly.

The other thing to look for is brown, thin, squishy roots which indicates rotting roots, probably due to overwatering. Don’t buy such plants even if the top growth looks good. When a plant dies, the roots normally go first.

One of the reasons gardeners don’t understand roots very well is that once they are planted in the garden, they never see what roots are doing. You don’t see root growth slowing down in mid-summer because temperatures are too high, or that they do much of their growing in fall when it is cooler. You also can’t see the damage caused by daily watering or by drought conditions. At best we infer plant health by looking at top growth but root decline is normally a slow process and it can take weeks or even months to show above ground.

The more you know about roots, the better you will be able to take care of your plants.

Root Basics

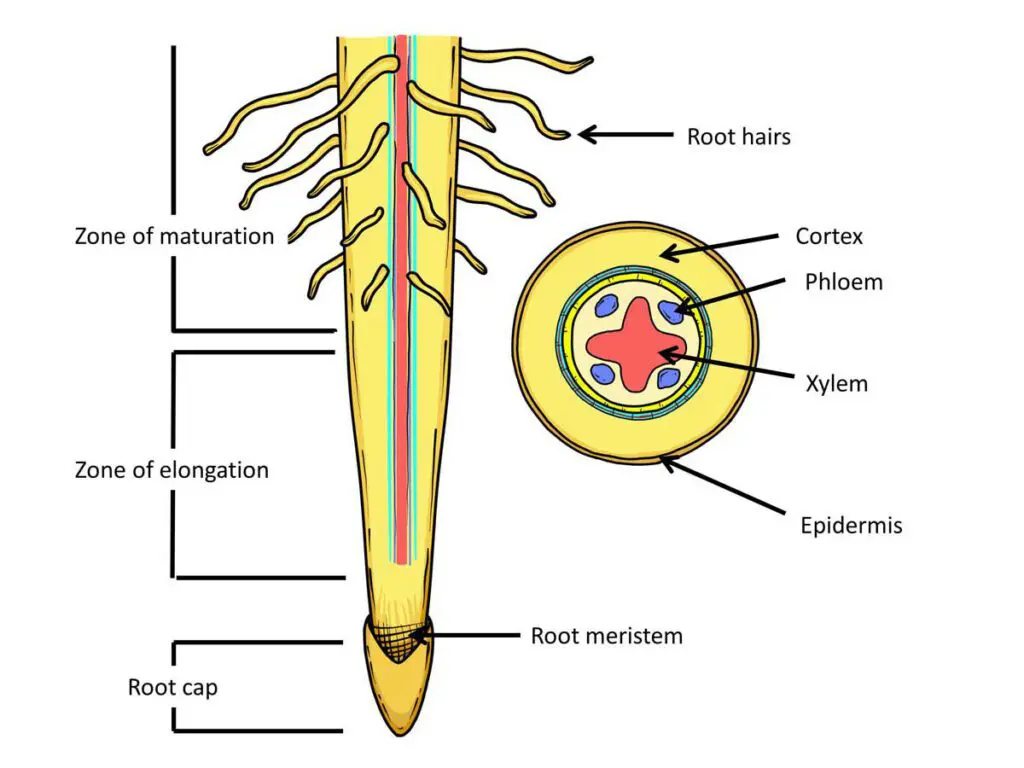

Roots are plant structures that typically grow underground to stabilize the plant and obtain resources from the soil. The basic structure of a root consists of the epidermis, root cap, root hairs, cortex and vascular bundle. Root systems are highly productive and can be many times larger than the top growth.

Roots are critical to the survival of almost all plants.

They anchor plants in place and obtain water and minerals from the soil. Roots help plants survive winter and other harsh environmental conditions by storing water, nutrients and carbohydrates. They can also contribute to asexual reproduction by producing root suckers or root sprouts which can become independent plants.

Epidermis

The epidermis is an outer layer of cells that surround the root. It functions as the skin of the root and allows water and nutrients to travel from the outside to the inside of the root. It also controls the movement of plant-produced chemicals, collectively called “exudates,” to travel out of the root.

The epidermis also allows oxygen to move into the root, which is critical for respiration.

Cortex and Vascular Bundle

In simple terms the inside of a root can be divided into the cortex and the vascular bundle (xylem and phloem). The primary function of the cortex is to conduct molecules between the epidermis and the xylem and phloem. In thicker roots it is also important for storing carbohydrates produced by the leaves. A mature carrot root is mostly a thick cortex full of these carbohydrates.

The xylem moves water and nutrients from the soil to all other parts of the plant, while the phloem moves minerals, proteins, sugars and other photosynthates from the upper plant to the roots.

Root Hairs

Gardeners talk about roots absorbing water and nutrients but it is actually the root hairs that do most of this. Root hairs look like very fine white hairs coming out of the roots. They tend to be too small to see them in most soil, but they are very visible on newly germinated seedlings.

Root hairs are an extension of the root epidermis. Most are formed near the root tips and they only last a couple of weeks. After that, the root aborts them and grows new ones closer to the root tip. A plant’s ability to replace them quickly is important for its survival. For example, if things get too dry, the plant aborts the root hairs, but keeps the roots. When enough moisture returns the plant quickly grows new root hairs to make use of the water.

Why does a plant make root hairs? Why not just rely on the root? By growing thin root hairs the plant has dramatically increased its root surface area. More surface area means more access to water and nutrients. Root hairs are hundreds of times more efficient at collecting water and nutrients than roots alone.

Root Cap

The root cap consists of several layers of cells in a dome formation that forms a thimble-like covering over the very tip of the root. The root cap protects the sensitive new tissues of the root tip from damage and infection as the root elongates and pushes through the soil. It functions similarly to the cap on a pen protecting the tender tip. The outer layer of the root cap is made up of dead cells that get rubbed off by soil friction, only to be replaced by new cells.