Over the past fifty years, we’ve made great strides in reducing extreme poverty, but nearly half the world’s population still lives on less than $4 a day. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has pushed many back into hardship. Low-income countries are now facing the tough challenge of tackling both poverty and climate change, all while dealing with heavy debt and a tricky global trade system. In this excerpt from Earth for All, the authors explore the systemic barriers to meaningful progress, from restrictive debt burdens to an unsustainable global trade architecture, and highlight the urgent need for innovative solutions that empower nations to thrive in an increasingly unpredictable world.

From Saying Goodbye to Poverty

What Is Our Current Problem?

Extreme poverty has declined dramatically in the last fifty years. But still almost half the world lives in poverty, surviving on less than $4 per day (equal to a GDP per person of some $1,500 per year). Pre-pandemic estimates on meeting global targets such as the Sustainable Development Goal 1 (eradicating extreme poverty) required low-income countries to grow at an average annual rate of 6%, and the consumption (or income) of the bottom forty countries needed to grow 2% faster than the average. COVID-19, however, is estimated to have set back progress on poverty by six or seven years. New economic estimates, accounting for COVID-19, indicate that up to 600 million could be living in extreme poverty by 2030 if economic development goes back to “business as usual.” Compounding this, the current economic system places low- and middle-income countries in a position where they must choose between addressing poverty and addressing climate change.

Issue 1: A Shrunken Policy Space

The policy space for governments seeking to act on both poverty and global warming is severely restricted by the global economic system. The free flow of finance is blocked by heavy debt-repayment restrictions. Through institutions like the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank, rich countries exert strong control over the finances of low-income countries, and extract considerable interest payments from them, leaving them with limited funds to invest in their own country. And foreign investors often extract more capital (when accounting for human and natural capital) than they interject. In the end, policies originally conceived to reduce poverty have either failed or, worse, exacerbated it.

Low-income countries lack funds (and savings) to invest in key development projects or infrastructure, such as power grids, water supply, roads, rails, and hospitals. More of these investments could spur a healthy growth model. Lack of such infrastructure, particularly electricity, causes African countries to lose up to 3 to 4% of growth per year, notes Masse Lô, founder and CEO, Institute of Leadership for Development, in an Earth for All Deep Dive paper.

In many low-income countries, foreign investment is seen as a key solution. But the current global system encourages markets, rather than governments, to allocate the necessary funds or liquidity (cash) to these countries. To add insult to injury, these funds are in foreign currencies that means scarce financial resources being allocated to servicing ever-growing mountains of debt. This includes finance coming from other countries or multinational corporations.

This attitude is actively fostered by the global economic bodies. Governments are encouraged to have their economies completely open to capital flows. Highly mobile international capital can park itself in a country or sector it sees as profitable, but there is no guarantee that such funds will be invested either in poverty alleviation or in building energy-efficient capacity. Usually, this liquidity ends up in the financial sector of the economy, among stocks and derivatives, which are potentially quick to withdraw.

Foreign capital has modest to little impact on economic development, growth, or welfare in many countries. Further, foreign capital often displaces (or crowds out) domestic investment or drives up greenhouse gas emissions and pollution. Footloose finance, which is essentially looking to make a quick profit, is unlikely to be invested in the long-term projects that would address the development needs or clean energy capacity of a country. The investments for those purposes have to be intentional, coordinated, and strategic—goals that domestic economic policy stands a much better chance of meeting.

For some low-income countries, the reduced maneuverability from global structures is worsened by a large part of available resources being directed toward debt and interest payments. In 2020, debt in low- and middle-income countries rose to $8.7 trillion according to the World Bank. Of this, the debt burden of the world’s low-income countries rose 12% to a record $860 billion. Most of this was related to pandemic needs.

According to economist Richard Wolff, thirty-four of the poorest countries now pay far more in debt repayment (chiefly to rich countries) than they spend on the climate crisis. Similarly, the spending on healthcare during the pandemic has suffered. And as the debt burden rocketed in many low-income countries, their economic growth was stalling. Other countries, in seeking to stick to traditional recommendations by multilateral institutions, may maintain a very low debt burden. But they are only able to do so by limiting their expenditure on welfare schemes or on large capital-intensive green investments.

Issue 2: Destructive Trade Architecture

The expansion of global trade has naturally led to concerns about how much carbon dioxide is emitted at the various stages of production, transportation, and consumption of goods and services. Supporters of the current free trade model argue that the current global trade architecture is compatible with poverty and climate goals under the right circumstances. Just shift trade to favor cleaner producing countries, and use it to motivate polluting countries to adopt technological solutions.

This can only happen, however, if high-income countries acknowledge the structural hurdles that prevent such actions from occurring. In actuality, the current global trade architecture hinders a shift to addressing both climate and poverty.

High-income countries outsource their production to low-income countries to benefit from reduced costs while low-income countries benefit from increased jobs and wages to their many workers. But outsourcing has brought heavily polluting industries and more climate emissions to low-income countries. When assigning responsibility, however, the current standard method for determining carbon emissions is based on emissions within a country’s boundaries, notes Earth for All Transformational Economics Commissioner Jayati Ghosh and team. There is no accountability for consumption emissions.

The outcome of this process has been that high-income countries have been able to exploit cross-border trade to effectively “export” emissions to producing countries. The latter have now been tasked with the responsibility of cleaning up these exported emissions, but under stiff global competition. However, when countries attempt to clean up—through national regulations, protectionist measures, or controls on the importation of recyclable waste, for instance—they are then unfairly criticized for opposing free trade. And oftentimes taken to court.

This lack of distinction between consumption-based emissions and production-based emissions not only allows high-income countries to bypass responsibility, it also places the burden of potential tariffs on low-income countries, without providing them the knowledge/ technology or financial resources to measure and control emissions. For instance, carbon border taxes aim to control emissions by taxing imports on goods produced in high-emission countries. Again, this shifts the monetary benefit to the high-income consumers rather than the low-income producers that are filling their demand for material goods.

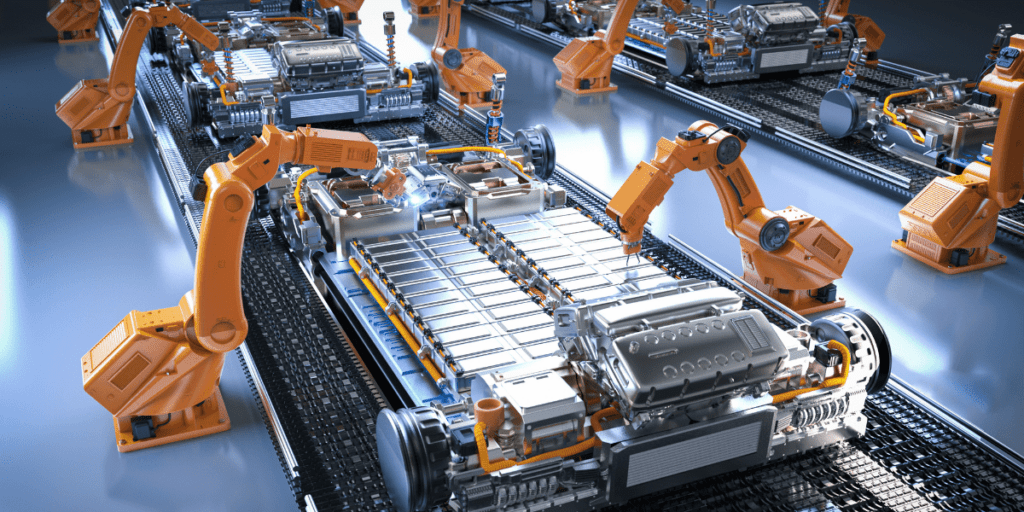

Issue 3: Hurdles to Technological Access

From advanced materials to renewable energy, new technologies are key to solving global warming. Practically every model of climate response envisages some role for both existing and future forms of technology to cut emissions and environmental degradation. Unfortunately, much of this green technology is inaccessible. This is not due to technological infeasibility. It happens because the frameworks for tech transfer do not allow low-income countries to use them. From restrictive intellectual property laws to prohibitively expensive access in hard currencies, low-income countries that desperately need such technology to green their operations, bring vaccines to their poor, or reduce expenses cannot access it. Countries in need, who have already constrained financial policy space, are then further squeezed and compelled either to accept bad terms of use or else forgo access to such technology.

For a closer look at innovative solutions to tackle the issue of poverty in low-income nations, read Earth For All for.