Michael G. Smith, co-author of Essential Cob Construction: A Guide to Design, Engineering, and Building has written three books on cob construction… Why would anyone write three books on the same topic, and could this ancient building technique possibly provide enough content to justify three books? Today, Michael addresses just how and why he wrote Essential Cob Construction in addition to his previous two books.

It’s Time for Cob Building to Come out of the Woods

I am probably the first person in history to have written or co-written three books on cob construction, an ancient method of earthen building that has been enjoying a revival of interest around the world since the 1990s. This somewhat dubious achievement demands justification. Why would anyone write three books on the same apparently marginal topic?

My first book, The Cobber’s Companion, was self-published in 1997. This was the first instructional manual on cob building ever published in English (or any other language as far as I know). And believe it or not, in that long ago pre-YouTube era, books were the primary method of sharing technical information. My colleagues Ianto Evans and Linda Smiley, with whom I started the Cob Cottage Company in Oregon in 1993, had taken a bicycle tour through parts of Wales and England in the late 1980s looking at old cob buildings and trying unsuccessfully to find anyone with first-hand knowledge of how they had been built. After thriving since time immemorial, the cob tradition in Britain appeared to be defunct. Scouring used bookstores and architectural libraries, they unearthed only a few chapters in old books on “the quaint country cottage” written by architects and historians with no personal earth-building experience. For centuries, it seems, the categories of “people who write books” and “people who build cob houses” had been mutually exclusive.

There was a surprising amount of interest in my little book, and in the hands-on cob workshops we were teaching all around the Western United States and British Columbia. The booklet found its way to a publisher, Chelsea Green, who approached Ianto, Linda, and me about an expanded volume. The Hand-Sculpted House came out in 2002 and has sold over fifty thousand copies. With the subtitle, A Practical and Philosophical Guide to Building a Cob Cottage, the book explains to readers not only how to design and build a small earthen house, but why. Even though we had been building with and teaching cob for less than a decade at the time of its publication, we thought we understood our audience and their motivations pretty well. They were people who wanted to drop out of the rat race, move to the country, plant a garden, and homeschool their kids. We targeted our instructions to first-time builders with very little money but enough free time to build their own homes from scratch.

And, crazy at it seems, the book–along with practical workshops taught by the Cob Cottage Company and others—worked! I have met dozens of people who built small, functional, and beautiful homes for their families mainly by following the guidelines in The Hand-Sculpted House. One man stands out in my memory as a striking example. A Spanish expat living in Nicaragua, he had actually taught himself to read English and to build a house at the same time–from our book!

In the decades since The Hand-Sculpted House was written, the world has changed in profound ways. Thanks to the internet, there is exponentially more information available from all around the globe than 30 years ago. It turns out that cob building is not just a British phenomenon but a nearly global tradition. My list of regions with a known history of cob has grown to include most of Europe, North and West Africa, the Middle East, India and surrounding countries, scattered areas of East Asia and Latin America, and even pre-Columbian North America. In some cases, the cob tradition continues unbroken to this day, passed down generation to generation out of the distant past. In places like the Punjab, Yemen, and Oaxaca, Mexico, people have been cobbing away all the time – without any need for books at all!

Here in the US, “green building” has evolved from the exclusive purview of hippies in the woods to a big business dominated by architectural firms, policymakers, researchers, and manufacturers. For a long time, cob seemed to revolve in its own little eddy outside of this mainstream. And I was fine with that! I and like-minded sticks-in-the-mud were concerned that if someone were to figure out how to make money off cob construction, it would lose a lot of its value. Our interest in cob was motivated as much by the social benefits of deconsumerism and owner-building as by the environmental advantages of locally harvested, low-embodied-energy materials. So even after joining the board of a startup non-profit called the Cob Research Institute, dedicated to writing a cob building code and removing institutional barriers to cob construction, I remained privately ambivalent. Building codes? Engineers? Who needs ‘em? The Revolution will not apply for a building permit!

Looking back, I can watch my attitude changing bit by bit. One memorable realization hit in November of 2018. Much of Northern California, where I live, was engulfed in a plume of toxic smoke from the Camp Fire, which consumed the towns of Paradise and Concow along with 154,000 acres of forest land. More than 10,000 families lost their homes. I remember thinking, if all those houses had been built of earth (with other fire-resistant materials and designs) they might not have burned down, all those people might not be displaced, and my family might not be breathing the pernicious residues of vaporized plastics, carpets, insulation materials, and other industrial building components. The human and environmental benefits would be enormous no matter who had built these hypothetical earthen houses or how much money they had made.

Another watershed moment happened a year later at the International Code Council’s public hearings in Las Vegas, when a startling majority of ICC members (mainly US building and fire officials) voted to adopt the Cob Construction Appendix into the International Residential Code. (You can find out more about the Appendix and the research that led to it at cobcode.org.) Although my colleagues at the Cob Research Institute were not surprised by this result, I was still caught up in an imaginary conflict between “the Earth” and “the Man.” It turns out that many of those officials were also interested in less-toxic, less-flammable, less environmentally damaging building systems. Who would have thunk it?

Before the model cob building code could be written, a great deal of research had to be done to prove that properly designed and carefully built cob buildings could perform well in earthquakes and other extreme events. The testing was conducted by a large team of volunteers including engineers, architects, university professors, and students. Like the building officials, these academics and professionals turned out not to be cob’s enemies, but its dedicated supporters. And after all of this research had been done, and the code written, it made sense to collect and interpret it all in one place where anyone who may be interested – contractors and owner-builders, designers, engineers, academics, building inspectors, policymakers, and homemakers – can access and understand it.

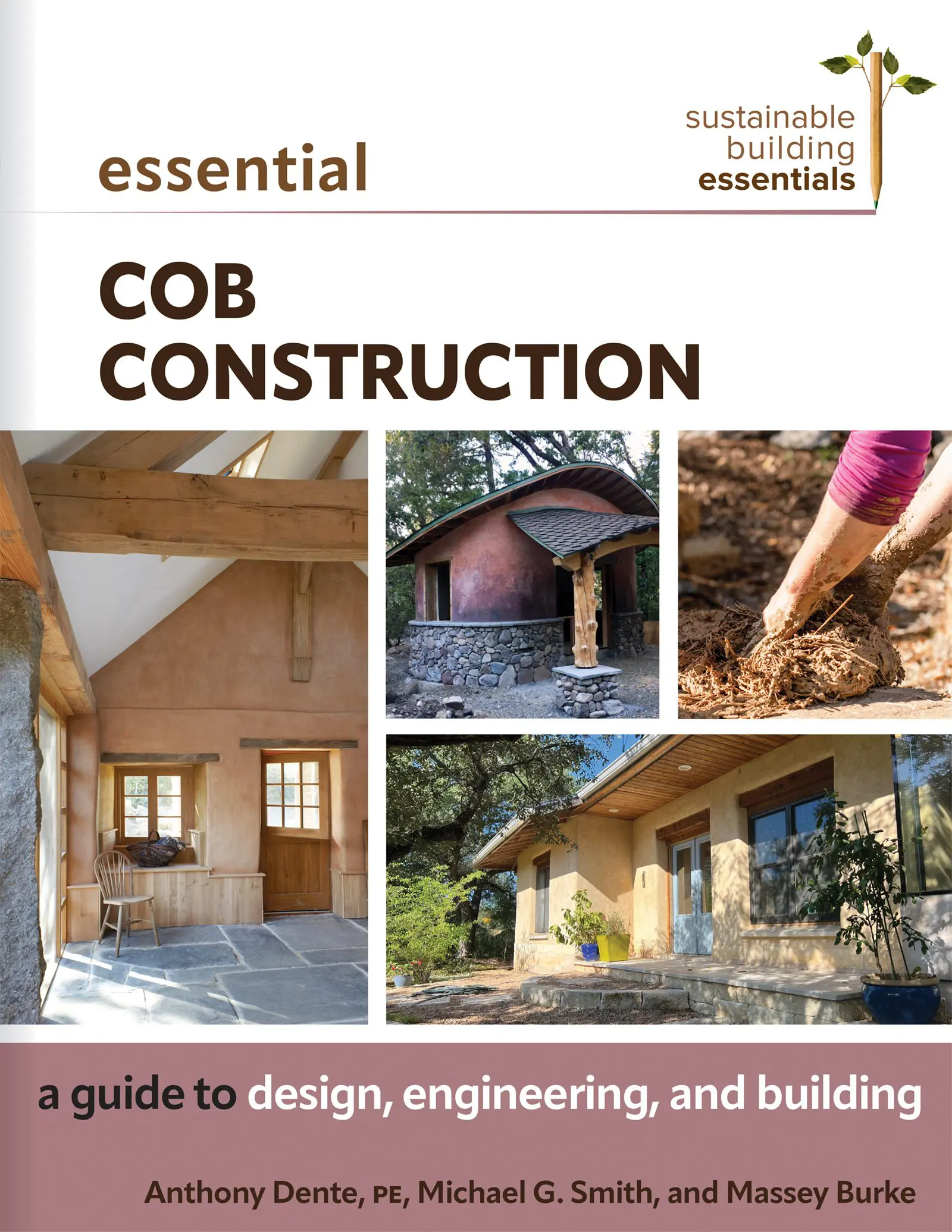

So that brings me to my latest book, Essential Cob Construction, just released this month by New Society Publishers and co-written with engineer Anthony Dente and designer/builder/sustainability advocate Massey Burke, both of whom have played critical roles in cob’s formalization. Far from being a rehash of The Hand-Sculpted House, most of its contents are completely new. It includes in-depth chapters on cob-related building science, structural engineering, building codes, budgeting, mix design, and testing that have never been written about before. Even the how-to chapters on cob mixing and building are updated with recent developments such as mechanical mixing techniques, appropriate reinforcement, insulation options, and the use of formwork. Many of these recommendations emerged from interviews with professional cob builders in several countries.

I no longer believe I know just who my audience is. Cob isn’t nearly so marginal a subject as I once thought. I have been surprised over the years that all kinds of people are enthusiastic about earthen building. Now that there is a model building code for cob, it is time for this time-proven technique to come out from hiding in the woods and see what other opportunities await. We wrote this book to help that happen. Even people who live in the city or the suburbs, have full-time jobs, plan to hire an architect and a contractor, require a building permit, home insurance, or a bank loan, may be perfect candidates for cob homes. If you fall into any of those categories (or, most likely, many others I haven’t thought of), this book is for you!