Today’s world, for many of us, has become increasingly tech-focussed. We start and end our days focussed on phones, tablets, and computers, surfing news and social media. While a complete disconnection from technology – specifically, the internet – is unrealistic for most of us, taking breaks to re-engage in the real world is increasingly important as our physical and mental health struggles to keep up with the constant flow of information.

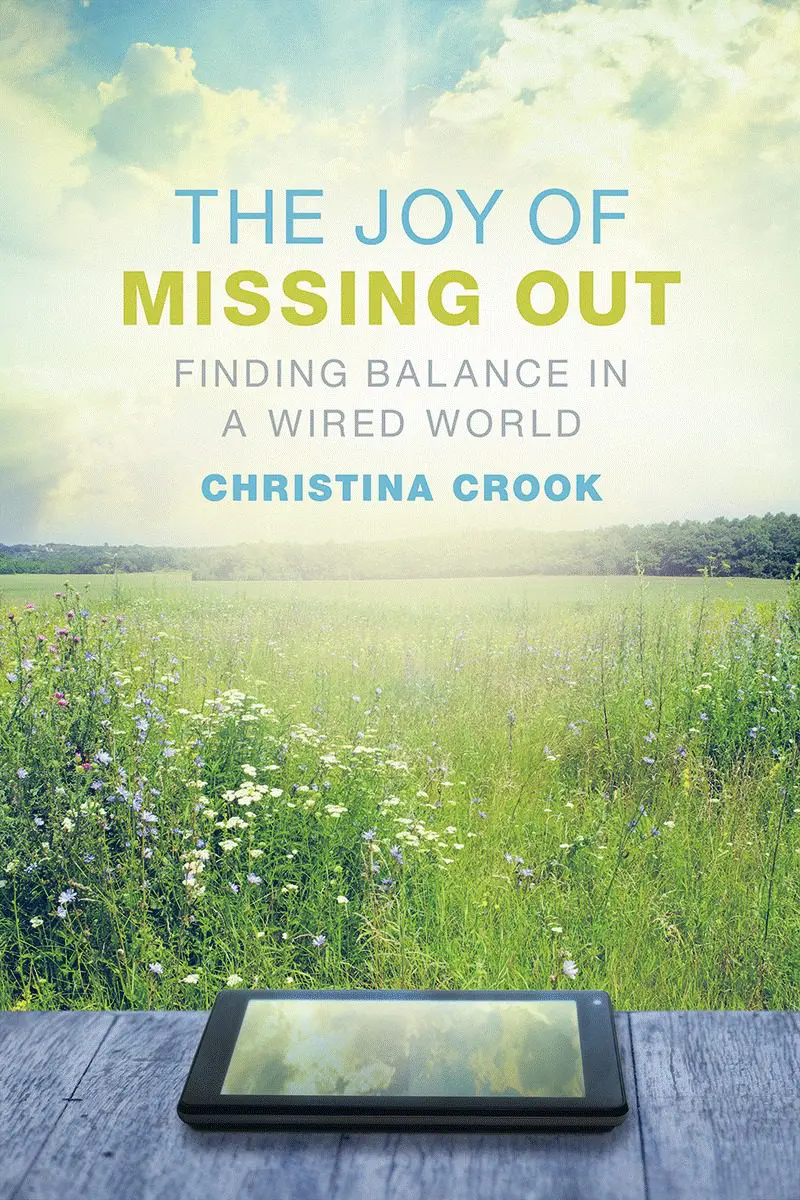

In The Joy of Missing Out, author Christina Crook delves into the impacts our wired world is having on us individually and as a society, and suggests achievable options for taking breaks and reclaiming our control over technology, rather than slipping back into ceding control to it.

Why Fast the Internet?

We are embodied beings. Since we communicate through body language long before we ever learn to talk, the language of gesture and eye contact is our original language. As we grow, we add words to our arsenal but language of the body remains our primary means of understanding and expression.

From birth, the eyes of humans by nature seek out the eyes of others. What happens when that gaze is broken so permanently that people don’t know how to connect with each other anymore? What are the ramifications for empathy? For sexual intimacy? For parenthood? Too rarely we stop to consider: what is this new thing for? What is it replacing? Where will I find the resources or time to engage with it? How much is enough? We fast to begin asking these questions.

In a March 2014 article in The New Yorker titled “The Pointlessness of Unplugging,” Casey Cep argues that “the unplugging movement, which encourages us to disconnect from technology, is unsustainable and misguided.” Let us consider another proposition: The Internet-addiction movement, which encourages us to connect online at all times in all places, is unsustainable and misguided. Which is more accurate?

There are no simple answers here, to be sure. The terms “disconnecting,” “unplugging,” and “digital detox,” are limiting because they suggest that offline/online worlds are separate when, increasingly, they are not. But these terms are a starting point as we personally and collectively navigate uncharted waters. Some people have a better time finding balance in their lives when it comes to using digital technologies, but others of us have a harder time striking a balance. Taking a break, carving out space without a screen, helps us lift our eyes, to engage in different ways that, for many, is life-giving. Washington University psychiatrist C. Robert Cloninger says: “You’re going to be confronted with many stimuli designed to grab your attention and addict you, so you should be very careful about what you expose yourself and your children to. Everyone needs time for quiet, reflection and reverie. You have to achieve an equilibrium between those deep human needs and other stimuli, or you’ll have problems.”

Suggesting that to unplug for a few days is pointless because people plan to return to the digital world is misguided. By that logic, we should also rid ourselves of weekends, summer vacations, fasting for religious or health purposes and giving up drugs.

We — you and I — have traded communing, being with people in the real world, for a counterfeit. But we can shift things simply. We can set our smartphones aside and set limits on our technology use — and this discipline can lead to our joy.

We must remind ourselves and reveal to our children the wonder found only in the real world: the beauty and peace in the stillness of the outdoors; the sense of accomplishment and joy in writing a letter to a loved one; the sheer delight of sitting around and playing a ridiculous board game. These are the things that will motivate us to set aside our smartphones, close the lids on our laptops and pay attention to the world in front of us.

And why is it imperative that we model and teach this to the young people in our lives? Because we can remember a time before the smartphone; they can’t. We can and must be deliberate in our consumption now, in our workplaces, in our friendships and in our homes. Present people, people who look you straight in the eye, are a rare and wonderful breed. Imagine being that kind of executive, that kind of parent, that kind of teacher, that kind of friend.

It is within our grasp.